10/03/2011

Algebre PCSI PTSI , Cours, méthodes et exercices corrigés Jean-Marie Monier Etude (broché). Paru en 04/2007

19:50 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Algèbre 1 cours et 600 exercices corrigés , 1re année MPSI PCSI PTSICours de mathématiques T5 Jean-Marie Monier (donnée non spécifiée). Paru en 04/1996

19:49 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Annabrevet sujets Mathématiques toutes séries, Edition 2011 Collectif Scolaire / Universitaire (broché). Paru en 08/2010

19:43 Publié dans Brevet des collèges, Corrigés | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Annabrevet corrigés la compil' , Edition 2011 Collectif Scolaire / Universitaire (broché). Paru en 08/2010

19:41 Publié dans Annabrevet, Brevet des collèges | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

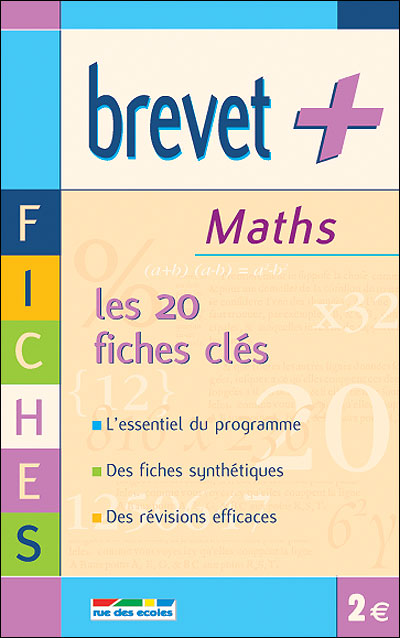

100% Brevet Mathématiques , Les fiches Collectif Scolaire / Universitaire (broché). Paru en 01/2006

19:40 Publié dans Brevet des collèges | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Annabrevet corrigés Mathématiques , Edition 2006 Collectif Scolaire / Universitaire (broché). Paru en 09/2005

19:38 Publié dans Annabrevet, Brevet des collèges, Corrigés | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Problèmes corrigés de mathématiques posés aux concours communs Polytechniques , T10 Jean Franchini, Jean-Claude Jacquens

19:36 Publié dans Corrigés | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les maths expliquées aux parents Alain Gastineau Scolaire / Universitaire (poche). Paru en 02/2011

19:35 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

500 exercices corrigés de mathématiques pour l'économie et la gestion Alain Gastineau Etude (relié). Paru en 02/2007

19:33 Publié dans Corrigés | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Exercices corrigés de mathématiques 1ère et 2ème année de classe prepa économie Karine Madère Scolaire / Universitaire (broché). Paru en 07/2001

19:32 Publié dans Corrigés | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Mathématiques 1ère S Collectif Scolaire / Universitaire (broché). Paru en 07/2009

19:30 Publié dans 1ère S | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Mathématiques série ES annales corrigées, Obligatoire et spécialité Collectif Scolaire / Universitaire (broché). Paru en 08/2007 Livre

19:29 Publié dans Corrigés | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

L'algèbre arabe , Genèse d'un art Ahmed Djebbar, Bernard Maitte Essai (broché). Paru en 06/2005 Livre

19:27 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Méthodix algèbre , 250 méthodes 250 exercices corrigés Xavier Merlin Scolaire / Universitaire (broché). Paru en 05/1998 Livre

19:26 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Algèbre sur un corps

Source : http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alg%C3%A8bre_sur_un_corpsAlgèbre sur un corps

|

|

Cet article est une ébauche concernant les mathématiques.

Vous pouvez partager vos connaissances en l’améliorant (comment ?) selon les recommandations des projets correspondants.

|

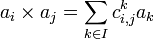

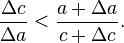

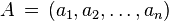

En mathématiques, une algèbre sur un corps commutatif K, ou simplement une K-algèbre, est une structure algébrique (A , + , . , × ) telle que : Soient K un corps commutatif et A un espace vectoriel sur K muni de plus d'une opération binaire (c'est-à-dire que le « produit » x×y de deux éléments de A est un élément de A. On dit que A est une algèbre sur K si cette opération binaire est distributive par rapport à + et bilinéaire, ce qui signifie que pour tous vecteurs x, y, z dans A et tous scalaires a, b dans K, les égalités suivantes sont vraies : On dit que K est le corps de base de A. L'opérateur binaire est souvent désigné comme la multiplication dans A. Deux algèbres A et B sur K sont isomorphes s'il existe une bijection Dans la définition, K peut être un anneau commutatif unitaire, et A un K-module. Alors, A est encore appelée une K-algèbre et on dit que K est l'anneau de base de A. Une algèbre associative est une algèbre sur un anneau dont la loi de composition interne x est associative. Lorsque cet anneau est un corps, il s'agit donc d'une Une algèbre est dite unifère si elle admet un élément neutre 1 pour la multiplication x. Une algèbre est dite commutative, si la loi de composition interne x est commutative. Tout espace vectoriel admet une base. Une base d'une algèbre A sur un corps K est une base de A pour sa structure d'espace vectoriel1. Si Pour i et j fixés, les coefficients sont nuls sauf un nombre fini d'entre eux. On dit que Une base de l'algèbre Par exemple le corps fini Une telle algèbre est appelée algèbre quadratique de type (a, b) (le type dépendant de la base choisie). La table de multiplication dans une base orthonormale directe (![]() Pour les articles homonymes, voir Algèbre (homonymie).

Pour les articles homonymes, voir Algèbre (homonymie).

Définitions[modifier]

telle que

telle que

Bases et tables de multiplication d'une algèbre sur un corps[modifier]

est une base de A, il existe alors une unique famille

est une base de A, il existe alors une unique famille  d'éléments du corps K tels que :

d'éléments du corps K tels que : .

.

sont les constantes de structure1 de l'algèbre A par rapport à la base a, et que les relations

sont les constantes de structure1 de l'algèbre A par rapport à la base a, et que les relations  constituent la table de multiplication de l'algèbre A1.

constituent la table de multiplication de l'algèbre A1.Exemples d'algèbres de dimension finie[modifier]

est une

est une  - algèbre associative, unifère et commutative de dimension 2.

- algèbre associative, unifère et commutative de dimension 2. est constituée des éléments 1 et i. La table de multiplication est constituée des relations :

est constituée des éléments 1 et i. La table de multiplication est constituée des relations :

), donc son ordre est pn.

), donc son ordre est pn. est une algèbre de dimension 2 sur le corps

est une algèbre de dimension 2 sur le corps  dont la table de multiplication dans une base (1, a) est :

dont la table de multiplication dans une base (1, a) est :

à valeur dans

à valeur dans  ,

,  est une

est une  - algèbre associative, unifère et non commutative de dimension n2.

- algèbre associative, unifère et non commutative de dimension n2. est une

est une  - algèbre associative, unifère et non commutative de dimension 4.

- algèbre associative, unifère et non commutative de dimension 4. est une

est une  -algèbre associative, unifère et non commutative de dimension 4 qui est isomorphe à l'algèbre

-algèbre associative, unifère et non commutative de dimension 4 qui est isomorphe à l'algèbre  des matrices matrices carrées d'ordre 2 à valeur dans

des matrices matrices carrées d'ordre 2 à valeur dans  .

.

est une

est une  - algèbre unifère non associative et non commutative de dimension 8.

- algèbre unifère non associative et non commutative de dimension 8.

muni du produit vectoriel

muni du produit vectoriel  est une

est une  - algèbre non associative, non unifère et non commutative (elle est anti-commutative) de dimension 3.

- algèbre non associative, non unifère et non commutative (elle est anti-commutative) de dimension 3. ,

,  ,

,  ) est :

) est :

à valeur dans

à valeur dans  , muni du crochet de Lie : [M,N] = MN − NM,

, muni du crochet de Lie : [M,N] = MN − NM, ![left(mathcal M_n(mathbb R), +,cdot, [,] right)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/4/9/e/49ebdc968ab715dec75900a90c652c57.png) est une

est une  - algèbre non associative, nonunifère et non commutative de dimension n2. Elle est anti-commutative et possède des propriétés qui font de l'algèbre une algèbre de Lie.

- algèbre non associative, nonunifère et non commutative de dimension n2. Elle est anti-commutative et possède des propriétés qui font de l'algèbre une algèbre de Lie.Contre-exemple[modifier]

n'est pas une

n'est pas une  -algèbre car la multiplication

-algèbre car la multiplication  n'est pas

n'est pas  -bilinéaire :

-bilinéaire :  .

.Voir aussi[modifier]

Notes et références[modifier]

Sommaire[masquer] |

, , |

, , |

, , |

|

, , |

, , |

, , |

|

, , |

, , |

, , |

x2 = a1 + bx |

, , |

, , |

, , |

, , |

, , |

, , |

, , |

, , |

, , |

19:24 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Algèbre

Source : http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alg%C3%A8bre L'algèbre, mot d'origine arabe al-jabr (الجبر), est la branche des mathématiques qui étudie les opérations et équations sur les nombres et plus généralement les structures algébriques. L'étude de ces structures peut être faite de manière unifiée dans la cadre de l'algèbre universelle. L'étude épistémologique de l'algèbre a été introduite par Jules Vuillemin. Les anciens Babyloniens et Égyptiens savaient déjà résoudre des problèmes qui peuvent être traduits en équations du premier ou second degré. Par exemple, le Papyrus Rhind (conservé au British Museum de Londres, il date de -1650, ère chrétienne) comporte l'énoncé suivant : Cependant, ils ne faisaient pas de l'algèbre, car ils n'effectuaient pas de calcul sur une inconnue. Diophante d'Alexandrie (vers 200/214 - vers 284/298), au IIIe siècle de l'ère chrétienne, fut le premier à pratiquer l'algèbre en introduisant le concept d'inconnue en tant que nombre,1 et à ce titre peut être considéré comme "le père" de l'algèbre. Le mot « algèbre » vient de l'arabe al-jabr (الجبر), qui est devenu algebra en latin et qui signifie « la réunion » (des morceaux), « la reconstruction » ou « la connexion » (en espagnol le mot algebrista désigne celui qui pratique le calcul algébrique mais aussi le rebouteux, celui qui sait réduire les fractures osseuses2). C'est un des premiers mots du titre en arabe d'un ouvrage du mathématicien d'origine persane Al-Khawarizmi. Le titre de cet ouvrage (Al-jabr wa'l-muqabalah) qui s'inscrivait dans l'époque d'essor des sciences et techniques islamiques (la culture de l'époque voulait que tout savoir soit traduit en arabe et disséminé dans tout l'Empire), a donné le mot moderne « algèbre ». Une large proportion des méthodes utilisées sont issues de résultats élémentaires de géométrie. Pour cette raison, on classe souvent ces premiers résultats dans la branche de l'algèbre géométrique. Après un voyage dans le nord de l'Afrique, Léonard de Pise dit Fibonacci fut séduit par cette nouvelle façon d'écrire les chiffres (différente des chiffres romains) et par le système décimal. Dès son retour au pays, il est parmi les premiers à populariser les chiffres arabes et le système décimal en Europe et travaille sur sa fameuse suite. Le pape Gerbert d'Aurillac avait ramené d'Espagne vers l'an 1000 le zéro, invention indienne que les mathématiciens Al-Khawarizmi et Abu Kamil avaient eux-mêmes fait connaître dans tout l'Empire, et aussi à Cordoue. Cette numération de position lance une ère de calcul algébrique, d'abord au moyen des algorithmes nommés ainsi en hommage à Al-Kawarizmi, qui remplacent peu à peu l'usage de l'abaque. Les mathématiciens italiens du XVIe siècle (del Ferro, Tartaglia et Cardan) résolvent l'équation du 3e degré (ou équation cubique).Ferrari, élève de Cardan, résout l'équation du 4e degré (ou équation quartique), et la méthode est perfectionnée par Bombelli. À la fin du siècle, le Français Viètedécouvre que les fonctions symétriques des racines sont liées aux coefficients de l'équation polynomiale. Jusqu'au xviie siècle, l'algèbre peut être globalement caractérisée comme la suite ou le début des équations et comme une extension de l'arithmétique ; elle consiste principalement en l'étude de la résolution des équations algébriques, et la codification progressive des opérations symboliques permettant cette résolution. C'est à François Viète (1540-1603) que l'on doit l'idée de noter les inconnues numériques à l'aide de lettres . Au XVIIe siècle, les mathématiciens utilisent progressivement des nombres « imaginaires », tels que l'une des racines carrées de -1, pour parvenir à calculer les racines non réelles de leurs équations. Cette « extension » des nombres réels (qui prendra le nom de nombres complexes) amène d'Alembert (en 1746) etGauss (en 1799) à énoncer et démontrer le théorème fondamental de l'algèbre (ou théorème de d'Alembert-Gauss) : Théorème — Toute équation polynomiale de degré n en nombres complexes a exactement n racines (en comptant chacune avec son éventuelle multiplicité). Sous sa forme moderne, le théorème s'énonce : Théorème — Le corps Le XIXe siècle s'intéresse désormais à la calculabilité des racines, et en particulier à la possibilité de les exprimer par des formules générales à base de radicaux. Les échecs concernant les équations de degré 5 amènent le mathématicien Abel (après Vandermonde, Lagrange et Gauss) à approfondir les transformations sur l'ensemble des racines d'une équation. Évariste Galois (1811 - 1832), dans un mémoire fulgurant, introduit pour la première fois la notion de groupe (en étudiant le groupe des permutations des racines d'une équation polynomiale) et aboutit à l'impossibilité de la résolution par radicaux pour les équations de degré supérieur ou égal à 5. Une étape décisive était franchie avec l'écriture des exposants fractionnaires. Celle-ci permettra à Euler d'énoncer sa célèbre formule eiπ + 1 = 0 liant cinq nombres remarquables. Dès lors, l'algèbre moderne entame un parcours fécond : Boole crée l'algèbre qui porte son nom, Hamilton invente les quaternions, et les mathématiciens anglais Cayley, Hamilton et Sylvester étudient les structures de matrices. L'algèbre linéaire, longtemps restreinte à la résolution de systèmes d'équations linéaires à 2 ou 3 inconnues, prend son essor avec le théorème de Cayley-Hamilton (« Toute matrice carrée à coefficients dans Au début du XXe siècle, sous l'impulsion de l'allemand Hilbert et du français Poincaré, les mathématiciens s'interrogent sur les fondements des mathématiques :logique et axiomatisation occupent le devant de la scène. Peano axiomatise l'arithmétique, puis les espaces vectoriels. La structure d'espace vectoriel et lastructure d'algèbre sont approfondies par Artin en 1925, avec des corps de base autres que L'école française « Nicolas Bourbaki », emmenée par Weil, Cartan et Dieudonné, entreprend de réécrire l'ensemble des connaissances mathématiques sur une base axiomatique : ce travail gigantesque commence par la théorie des ensembles et l'algèbre dans le milieu du siècle, et confirme l'algèbre comme langage universel des mathématiques. Paradoxalement, alors que le nombre de publications suit une croissance exponentielle à travers le monde, alors qu'aucun mathématicien ne peut prétendre dominer qu'une toute petite partie des connaissances, les mathématiques n'ont jamais autant paru unifiées qu'aujourd'hui.Algèbre

![]() Pour les articles homonymes, voir « Algèbre (homonymie) » et notamment la structure d'algèbre sur un anneau ou sur un corps.

Pour les articles homonymes, voir « Algèbre (homonymie) » et notamment la structure d'algèbre sur un anneau ou sur un corps.Histoire[modifier]

Antiquité[modifier]

Monde arabo-musulman[modifier]

XVIe siècle : Europe[modifier]

des nombres complexes muni de l'addition et de la multiplication est algébriquement clos.

des nombres complexes muni de l'addition et de la multiplication est algébriquement clos.Algèbre moderne[modifier]

ou

ou  annule son polynôme caractéristique »). S'ensuivent les transformations par changement de base, la diagonalisation et la trigonalisation des matrices, et les méthodes de calcul qui nourriront, au XXe siècle, la programmation des ordinateurs. Parallèlement, Kummer généralise les structures galoisiennes et étudie les structures de corps et d'anneau. Dedekind définit les idéaux (déjà entrevus par Gauss) qui permettront de généraliser et reformuler les grands théorèmes d'arithmétique. L'algèbre linéaire se généralise en algèbre multilinéaire et algèbre tensorielle.

annule son polynôme caractéristique »). S'ensuivent les transformations par changement de base, la diagonalisation et la trigonalisation des matrices, et les méthodes de calcul qui nourriront, au XXe siècle, la programmation des ordinateurs. Parallèlement, Kummer généralise les structures galoisiennes et étudie les structures de corps et d'anneau. Dedekind définit les idéaux (déjà entrevus par Gauss) qui permettront de généraliser et reformuler les grands théorèmes d'arithmétique. L'algèbre linéaire se généralise en algèbre multilinéaire et algèbre tensorielle. ou

ou  et des opérateurs toujours plus abstraits. On doit aussi àArtin, considéré comme le père de l'algèbre contemporaine, des résultats fondamentaux sur les corps de nombres algébriques. Les corps non commutatifs amènent à définir la structure de module sur un anneau et la généralisation des résultats classiques sur les espaces vectoriels.

et des opérateurs toujours plus abstraits. On doit aussi àArtin, considéré comme le père de l'algèbre contemporaine, des résultats fondamentaux sur les corps de nombres algébriques. Les corps non commutatifs amènent à définir la structure de module sur un anneau et la généralisation des résultats classiques sur les espaces vectoriels.Notations européennes modernes[modifier]

Voir aussi[modifier]

Notes et références[modifier]

Bibliographie[modifier]

Liens externes[modifier]

Sommaire[masquer] |

19:23 Publié dans Algèbre | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

08/03/2011

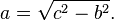

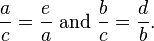

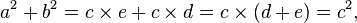

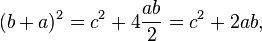

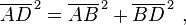

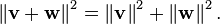

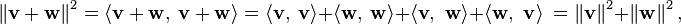

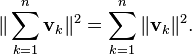

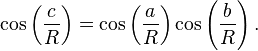

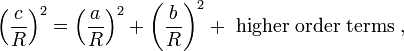

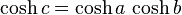

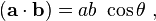

Pythagorean theorem

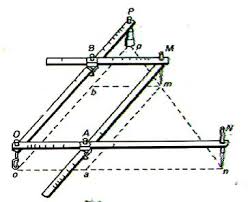

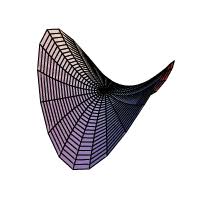

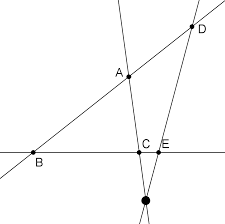

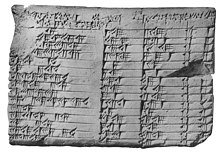

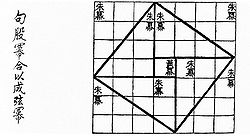

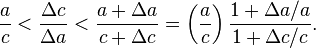

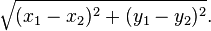

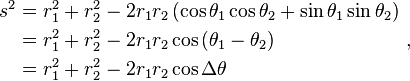

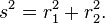

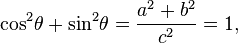

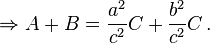

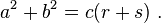

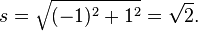

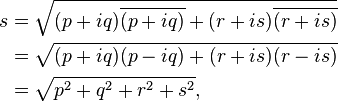

In mathematics, the Pythagorean theorem or Pythagoras' theorem is a relation in Euclidean geometry among the three sides of a right triangle (right-angled triangle). In terms of areas, it states: In any right triangle, the area of the square whose side is the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares whose sides are the two legs (the two sides that meet at a right angle). The theorem can be written as an equation relating the lengths of the sides a, b and c, often called the Pythagorean equation:[1] where c represents the length of the hypotenuse, and a and b represent the lengths of the other two sides. These two formulations show two fundamental aspects of this theorem: it is both a statement about areas and about lengths. Tobias Dantzigrefers to these as areal and metric interpretations.[2][3] Some proofs of the theorem are based on one interpretation, some upon the other. Thus, Pythagoras' theorem stands with one foot in geometry and the other in algebra, a connection made clear originally by Descartes in his work La Géométrie, and extending today into other branches of mathematics.[4] The Pythagorean theorem has been modified to apply outside its original domain. A number of these generalizations are described below, including extension to many-dimensional Euclidean spaces, to spaces that are not Euclidean, to objects that are not right triangles, and indeed, to objects that are not triangles at all, but n-dimensional solids. The Pythagorean theorem is named after the Greek mathematician Pythagoras, who by tradition is credited with its discovery and proof,[5][6] although it is often argued that knowledge of the theorem predates him. (There is much evidence that Babylonian mathematicians understood the formula, although there is little surviving evidence that they fitted it into a mathematical framework.[7]) "[To the Egyptians and Babylonians] mathematics provided practical tools in the form of 'recipes' designed for specific calculations. Pythagoras, on the other hand, was one of the first to grasp numbers as abstract entities that exist in their own right."[8] The Pythagorean theorem has attracted interest outside mathematics as a symbol of mathematical abstruseness, mystique, or intellectual power. Popular references to Pythagoras' theorem in literature, plays, musicals, songs, stamps and cartoons abound. As pointed out in the introduction, if c denotes the length of the hypotenuse and a and b denote the lengths of the other two sides, Pythagoras' theorem can be expressed as the Pythagorean equation: or, solved for c: If c is known, and the length of one of the legs must be found, the following equations can be used: or The Pythagorean equation provides a simple relation among the three sides of a right triangle so that if the lengths of any two sides are known, the length of the third side can be found. A generalization of this theorem is the law of cosines, which allows the computation of the length of the third side of any triangle, given the lengths of two sides and the size of the angle between them. If the angle between the sides is a right angle, the law of cosines reduces to the Pythagorean equation. This theorem may have more known proofs than any other (the law of quadratic reciprocity being another contender for that distinction); the book The Pythagorean Proposition contains 370 proofs.[9] This proof is based on the proportionality of the sides of two similar triangles, that is, upon the fact that the ratio of any two corresponding sides of similar triangles is the same regardless of the size of the triangles. Let ABC represent a right triangle, with the right angle located at C, as shown on the figure. We draw the altitude from point C, and call H its intersection with the side AB. Point H divides the length of the hypotenuse c into parts d and e. The new triangle ACH is similar to triangleABC, because they both have a right angle (by definition of the altitude), and they share the angle at A, meaning that the third angle will be the same in both triangles as well, marked as θ in the figure. By a similar reasoning, the triangle CBH is also similar to ABC. The proof of similarity of the triangles requires the Triangle postulate: the sum of the angles in a triangle is two right angles, and is equivalent to the parallel postulate. Similarity of the triangles leads to the equality of ratios of corresponding sides: The first result equates the cosine of each angle θ and the second result equates the sines. These ratios can be written as: Summing these two equalities, we obtain which, tidying up, is the Pythagorean theorem: This is a metric proof in the sense of Dantzig, one that depends on lengths, not areas. The role of this proof in history is the subject of much speculation. The underlying question is why Euclid did not use this proof, but invented another. One conjecture is that the proof by similar triangles involved a theory of proportions, a topic not discussed until later in the Elements, and that the theory of proportions needed further development at that time.[10][11] In outline, here is how the proof in Euclid's Elements proceeds. The large square is divided into a left and right rectangle. A triangle is constructed that has half the area of the left rectangle. Then another triangle is constructed that has half the area of the square on the left-most side. These two triangles are shown to be congruent, proving this square has the same area as the left rectangle. This argument is followed by a similar version for the right rectangle and the remaining square. Putting the two rectangles together to reform the square on the hypotenuse, its area is the same as the sum of the area of the other two squares. The details are next. Let A, B, C be the vertices of a right triangle, with a right angle at A. Drop a perpendicular from A to the side opposite the hypotenuse in the square on the hypotenuse. That line divides the square on the hypotenuse into two rectangles, each having the same area as one of the two squares on the legs. For the formal proof, we require four elementary lemmata: Next, each top square is related to a triangle congruent with another triangle related in turn to one of two rectangles making up the lower square.[12] The proof is as follows: This proof, which appears in Euclid's Elements as that of Proposition 47 in Book 1,[14] demonstrates that the area of the square on the hypotenuse is the sum of the areas of the other two squares.[15] It is therefore an areal proof in the sense of Dantzig, one that depends on areas, not lengths. This makes it quite distinct from the proof by similarity of triangles, which is conjectured to be the proof that Pythagoras used.[11][16] In the animation at the left, the total area and the areas of the triangles are all constant. Therefore, the total black area is constant. But the original black area of side c can be divided into two squares with sides a, b, demonstrating that a2 + b2 = c2. A second proof is given by the middle animation. An initial large square is formed of area c2 by adjoining four identical right triangles, leaving a small square in the center of the big square to accommodate the difference in lengths of the sides of the triangles. Two rectangles are formed of sides a and b by moving the triangles. By incorporating the center small square with one of these rectangles, the two rectangles are made into two squares of areas a2 and b2, showing that c2 = a2 + b2. The third, rightmost image also gives a proof. The upper two squares are divided as shown by the blue and green shading, into pieces that when rearranged can be made to fit in the lower square on the hypotenuse – or conversely the large square can be divided as shown into pieces that fill the other two. This shows the area of the large square equals that of the two smaller ones.[17] The theorem can be proved algebraically using four copies of a right triangle with sides a, b and c, arranged inside a square with side c as in the top half of the diagram.[19] The triangles are similar with area But this is a square with side c and area c2, so A similar proof uses four copies of the same triangle arranged symmetrically around a square with side c, as shown in the lower part of the diagram.[20] This results in a larger square, with side a + b and area (a + b)2. The four triangles and the square side c must have the same area as the larger square, giving A related proof was published by James A. Garfield.[21][22] Instead of a square it uses a trapezoid, which can be constructed from the square in the second of the above proofs by bisecting along a diagonal of the inner square, to give the trapezoid as shown in the diagram. The area of the trapezoid can be calculated to be half the area of the square, that is The inner square is similarly halved, and there are only two triangles so the proof proceeds as above except for a factor of One can arrive at the Pythagorean theorem by studying how changes in a side produce a change in the hypotenuse and employing calculus.[23][24] This proof is a metric proof in the sense of Dantzig, as it uses lengths, not areas. In the figure, triangle PBC is the original right triangle and triangle ABC is the modification of PBC when side PB is extended by increasing a to a + Δa. The circular arcs have radii c and c + Δc where Δc is the change in hypotenuse c that occurs as a result of the change Δa in side a. The figure shows two constructions, right triangles ADP and AQP, in the upper and lower panels which will be used to find respectively upper and lower boundsof the ratio Δc/Δa. Then the limit will be taken as Δa, Δc → 0, and the resulting expression for the derivative dc /da will be used to establish Pythagoras' theorem. From triangle ABC (upper panel), Construct right triangle ADP (upper panel). Then, The last inequality results from AD > Δc , as shown in the upper panel of the figure.[25] Combining the above expressions for cos θ, Next construct right triangle AQP (lower panel). Since both triangles AQP and PBC have an angle The last inequality results from PQ < Δc, as shown in the lower panel of the figure. Combining the two inequalities that were obtained using triangles ADP and AQP, We now have upper and lower bounds for the ratio Δc /Δa. As Δa, Δc → 0, the ratio Δc /Δa becomes the derivative dc /da and the upper bound becomes the same as the lower bounda /c. Consequently, or: which has the integral: When a = 0 then c = b, so the "constant" is b2. Hence, Pythagoras' theorem is established: Using this expression, the total differential is: This result shows that the increase in the square of the hypotenuse is the sum of the independent contributions from the squares of the sides. The converse of the theorem is also true:[26] For any three positive numbers a, b, and c such that a2 + b2 = c2, there exists a triangle with sides a, b and c, and every such triangle has a right angle between the sides of lengths a and b. Such numbers are called a Pythagorean triple. An alternative statement is: For any triangle with sides a, b, c, if a2 + b2 = c2, then the angle between a and b measures 90°. This converse also appears in Euclid's Elements (Book I, Proposition 48):[27] It can be proven using the law of cosines (see below under Generalizations), or by the following proof: Let ABC be a triangle with side lengths a, b, and c, with a2 + b2 = c2. We need to prove that the angle between the a and b sides is a right angle. We construct a second triangle with sides of lengths a and b containing a right angle. By the Pythagorean theorem, it follows that the hypotenuse of this triangle has length c = √(a2 + b2), which means the hypotenuse is the same length as the first triangle. Since both triangles have the same three side lengths a, b and c, they are congruent, and so they must have the same angles. Therefore, the angle between the side of lengths a and b in our original triangle also is a right angle. A corollary of the Pythagorean theorem's converse is a simple means of determining whether a triangle is right, obtuse, or acute, as follows. Where c is chosen to be the longest of the three sides and a + b > c (otherwise there is no triangle according to the triangle inequality). The following statements apply:[28] Edsger Dijkstra has stated this proposition about acute, right, and obtuse triangles in this language: where α is the angle opposite to side a, β is the angle opposite to side b, γ is the angle opposite to side c, and sgn is the sign function.[29] A Pythagorean triple has three positive integers a, b, and c, such that a2 + b2 = c2. In other words, a Pythagorean triple represents the lengths of the sides of a right triangle where all three sides have integer lengths.[1] Evidence from megalithic monuments in Northern Europe shows that such triples were known before the discovery of writing. Such a triple is commonly written (a, b, c). Some well-known examples are (3, 4, 5) and (5, 12, 13). A primitive Pythagorean triple is one in which a, b and c are coprime (the greatest common divisor of a, b and c is 1). The following is a list of primitive Pythagorean triples with values less than 100: One of the consequences of the Pythagorean theorem is that line segments whose lengths are incommensurable (that is, whose ratio is anirrational number) can be constructed using a straightedge and compass. Pythagoras' theorem enables construction of incommensurable lengths because the hypotenuse of a triangle is related to the sides via the square root operation. The figure on the right shows how to construct line segments whose lengths are in the ratio of the square root of any positive integer.[30] Each triangle has a side (labeled "1") that is the chosen unit for measurement. In each right triangle, Pythagoras' theorem establishes the length of the hypotenuse in terms of this unit. If a hypotenuse is related to the unit by the square root of a positive integer that is not a perfect square, it is a realization of a length incommensurable with the unit. Examples are √2, √3, √5 . For more detail, see Quadratic irrational. Incommensurable lengths conflicted with the Pythagorean school's concept of numbers as only whole numbers. The Pythagorean school dealt with proportions by comparison of integer multiples of a common subunit.[31] According to one legend, Hippasus of Metapontum (ca. 470 B.C.) was drowned at sea for making known the existence of the irrational or incommensurable.[32][33] The distance formula in Cartesian coordinates is derived from the Pythagorean theorem.[34] If (x1, y1) and (x2, y2) are points in the plane, then the distance between them, also called the Euclidean distance, is given by More generally, in Euclidean n-space, the Euclidean distance between two points, If Cartesian coordinates are not used, for example, if polar coordinates are used in two dimensions or, in more general terms, if curvilinear coordinates are used, the formulas expressing the Euclidean distance are more complicated than the Pythagorean theorem, but can be derived from it. A typical example where the straight-line distance between two points is converted to curvilinear coordinates can be found in theapplications of Legendre polynomials in physics. The formulas can be discovered by using Pythagoras' theorem with the equations relating the curvilinear coordinates to Cartesian coordinates. For example, the polar coordinates (r, θ) can be introduced as: Then two points with locations (r1, θ1) and (r2, θ2) are separated by a distance s: Performing the squares and combining terms, the Pythagorean formula for distance in Cartesian coordinates produces the separation in polar coordinates as: using the trigonometric product-to-sum formulas. This formula is the law of cosines, sometimes called the Generalized Pythagorean Theorem.[35] From this result, for the case where the radii to the two locations are at right angles, the enclosed angle Δθ = π/2, and the form corresponding to Pythagoras' theorem is regained: In a right triangle with sides a, b and hypotenuse c, trigonometry determines the sine and cosine of the angle θ between side a and the hypotenuse as: From that it follows: where the last step applies Pythagoras' theorem. This relation between sine and cosine sometimes is called the fundamental Pythagorean trigonometric identity.[36] In similar triangles, the ratios of the sides are the same regardless of the size of the triangles, and depend upon the angles. Consequently, in the figure, the triangle with hypotenuse of unit size has opposite side of size sin θ and adjacent side of size cos θ in units of the hypotenuse. The Pythagorean theorem was generalized by Euclid in his Elements to extend beyond the areas of squares on the three sides to similar figures:[37] If one erects similar figures (see Euclidean geometry) on the sides of a right triangle, then the sum of the areas of the two smaller ones equals the area of the larger one. The basic idea behind this generalization is that the area of a plane figure is proportional to the square of any linear dimension, and in particular is proportional to the square of the length of any side. Thus, if similar figures with areas A, B and C are erected on sides with lengths a, b andc then: But, by the Pythagorean theorem, a2 + b2 = c2, so A + B = C. Conversely, if we can prove that A + B = C for three similar figures without using the Pythagorean theorem, then we can work backwards to construct a proof of the theorem. For example, the starting center triangle can be replicated and used as a triangle C on its hypotenuse, and two similar right triangles (A and B ) constructed on the other two sides, formed by dividing the central triangle by its altitude. The sum of the areas of the two smaller triangles therefore is that of the third, thus A + B = C and reversing the above logic leads to the Pythagorean theorem a2 + b2 = c2. The Pythagorean theorem is a special case of the more general theorem relating the lengths of sides in any triangle, the law of cosines:[38] where θ is the angle between sides a and b. When θ is 90 degrees, then cosθ = 0, and the formula reduces to the usual Pythagorean theorem. At any selected angle of a general triangle of sides a, b, c, inscribe an isosceles triangle such that the equal angles at its base θ are the same as the selected angle. Suppose the selected angle θ is opposite the side labeled c. Inscribing the isosceles triangle forms triangle ABD with angle θ opposite side a and with side r along c. A second triangle is formed with angle θ opposite side b and a side with length s along c, as shown in the figure. Tâbit ibn Qorra[40] stated that the sides of the three triangles were related as:[41][42] As the angle θ approaches π/2, the base of the isosceles triangle narrows, and lengths r and s overlap less and less. When θ = π/2, ADBbecomes a right triangle, r + s = c, and the original Pythagoras' theorem is regained. One proof observes that triangle ABC has the same angles as triangle ABD, but in opposite order. (The two triangles share the angle at vertex B, both contain the angle θ, and so also have the same third angle by the triangle postulate.) Consequently, ABC is similar to the reflection ofABD, the triangle DBA in the lower panel. Taking the ratio of sides opposite and adjacent to θ, Likewise, for the reflection of the other triangle, Clearing fractions and adding these two relations: the required result. A further generalization applies to triangles that are not right triangles, using parallelograms on the three sides in place of squares.[43] (Squares are a special case, of course.) The upper figure shows that for a scalene triangle, the area of the parallelogram on the longest side is the sum of the areas of the parallelograms on the other two sides, provided the parallelogram on the long side is constructed as indicated (the dimensions labeled with arrows are the same, and determine the sides of the bottom parallelogram). This replacement of squares with parallelograms bears a clear resemblance to the original Pythagoras' theorem, and was considered a generalization by Pappus of Alexandria in 4 A.D.[43] The lower figure shows the elements of the proof. Focus on the left side of the figure. The left green parallelogram has the same area as the left, blue portion of the bottom parallelogram because both have the same base b and height h. However, the left green parallelogram also has the same area as the left green parallelogram of the upper figure, because they have the same base (the upper left side of the triangle) and the same height normal to that side of the triangle. Repeating the argument for the right side of the figure, the bottom parallelogram has the same area as the sum of the two green parallelograms. Pythagoras' formula is used to find the distance between two points in the Cartesian coordinate plane, and is valid if all coordinates are real: the distance s between the points (a, b) and (c, d) is No problem arises with the formula if complex numbers are treated as vectors with real components as in x + i y = (x, y). For example, the distance s between 0 + 1i and 1 + 0i becomes the magnitude of the vector (0, 1) − (1, 0) = (−1, 1), or However, a modification of the Pythagorean formula is necessary for a direct treatment of vectors with complex coordinates. The distance between the points with complex coordinates (a, b) and (c, d); a, b, c, and d all complex; is formulated using absolute values. The distance sis based upon the vector difference (a − c, b − d) in the following manner:[44] Let the difference a − c = p + i q, where p is the real part of the difference, q is the imaginary part and i = √(−1). Likewise, let b − d = r + is. Then: where The norm defined by: is a Hermitian dot product.[45] In terms of solid geometry, Pythagoras' theorem can be applied to three dimensions as follows. Consider a rectangular solid as shown in the figure. The length of diagonal BD is found from Pythagoras' theorem as: where these three sides form a right triangle. Using horizontal diagonal BD and the vertical edge AB, the length of diagonal AD then is found by a second application of Pythagoras' theorem as: or, doing it all in one step: This result is the three-dimensional expression for the magnitude of a vector v (the diagonal AD) in terms of its orthogonal components {vk} (the three mutually perpendicular sides): This one-step formulation may be viewed as a generalization of Pythagoras' theorem to higher dimensions. However, this result is really just the repeated application of the original Pythagoras' theorem to a succession of right triangles in a sequence of orthogonal planes. A substantial generalization of the Pythagorean theorem to three dimensions is de Gua's theorem, named for Jean Paul de Gua de Malves: If atetrahedron has a right angle corner (a corner like a cube), then the square of the area of the face opposite the right angle corner is the sum of the squares of the areas of the other three faces. This result can be generalized as in the "n-dimensional Pythagorean theorem":[46] This statement is illustrated in three dimensions by the tetrahedron in the figure. The "hypotenuse" is the base of the tetrahedron at the back of the figure, and the "legs" are the three sides emanating from the vertex in the foreground. As the depth of the base from the vertex increases, the area of the "legs" increases, while that of the base is fixed. The theorem suggests that when this depth is at the value creating a right vertex, the generalization of Pythagoras' theorem applies. In a different wording:[47] The Pythagorean theorem can be generalized to inner product spaces,[48] which are generalizations of the familiar 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional Euclidean spaces. For example, a function may be considered as a vector with infinitely many components in an inner product space, as in functional analysis.[49] In an inner product space, the concept of perpendicularity is replaced by the concept of orthogonality: two vectors v and w are orthogonal if their inner product The concept of length is replaced by the concept of the norm ||v|| of a vector v, defined as:[51] In this setting, the Pythagorean theorem states that for any two orthogonal vectors v and w of a normed inner product space, Here the vectors v and w are akin to the sides of a right triangle with hypotenuse given by the vector sum v + w. This form of the Pythagorean theorem is a consequence of the properties of the inner product: where the inner products of the cross terms are zero by orthogonality. A further generalization of the Pythagorean theorem in an inner product space to non-orthogonal vectors is the parallelogram law :[51] which says that twice the sum of the squares of the lengths of the sides of a parallelogram is the sum of the squares of the lengths of the diagonals. Any norm that satisfies this equality is ipso facto a norm corresponding to an inner product.[51] The identity can be extended to sums of more than two vectors. If v1, v2, ..., vn are pairwise-orthogonal vectors in an inner product space, application of the Pythagorean theorem to successive pairs of these vectors (as described for 3-dimensions in the section on solid geometry) results in the equation[52] Parseval's identity is a further generalization that considers infinite sums of orthogonal vectors. The Pythagorean theorem is derived from the axioms of Euclidean geometry, and in fact, the Pythagorean theorem given above does not hold in a non-Euclidean geometry.[53] (The Pythagorean theorem has been shown, in fact, to be equivalent to Euclid's Parallel (Fifth) Postulate.[54][55]) In other words, in non-Euclidean geometry, the relation between the sides of a triangle must necessarily take a non-Pythagorean form. For example, in spherical geometry, all three sides of the right triangle (say a, b, and c) bounding an octant of the unit sphere have length equal to π/2, which violates the Pythagorean theorem because a2 + b2 ≠ c2. Here two cases of non-Euclidean geometry are considered—spherical geometry and hyperbolic plane geometry; in each case, as in the Euclidean case for non-right triangles, the result replacing the Pythagorean theorem follows from the appropriate law of cosines. However, the Pythagorean theorem remains true in hyperbolic geometry and elliptic geometry if the condition that the triangle be right is replaced with the condition that two of the angles sum to the third, say A+B = C. The sides are then related as follows: the sum of the areas of the circles with diameters a and b equals the area of the circle with diameter c.[56] For any right triangle on a sphere of radius R (for example, if γ in the figure is a right angle), with sides a, b, c, the relation between the sides takes the form:[57] This equation can be derived as a special case of the spherical law of cosines that applies to all spherical triangles: By using the Maclaurin series for the cosine function, cos x ≈ 1 − x2/2, it can be shown that as the radius R approaches infinity and the arguments a/R, b/R and c/R tend to zero, the spherical relation between the sides of a right triangle approaches the form of Pythagoras' theorem. Substituting the approximate quadratic for each of the cosines in the spherical relation for a right triangle: Multiplying out the bracketed quantities, Pythagoras' theorem is recovered for large radii R: where the higher order terms become negligibly small as R becomes large. For a right triangle in hyperbolic geometry with sides a, b, c and with side c opposite a right angle, the relation between the sides takes the form:[58] where cosh is the hyperbolic cosine. This formula is a special form of the hyperbolic law of cosines that applies to all hyperbolic triangles:[59] with γ the angle at the vertex opposite the side c. By using the Maclaurin series for the hyperbolic cosine, cosh x ≈ 1 + x2/2, it can be shown that as a hyperbolic triangle becomes very small (that is, as a, b, and c all approach zero), the hyperbolic relation for a right triangle approaches the form of Pythagoras' theorem. On an infinitesimal level, in three dimensional space, Pythagoras' theorem describes the distance between two infinitesimally separated points as: with ds the element of distance and (dx, dy, dz) the components of the vector separating the two points. Such a space is called a Euclidean space. However, a generalization of this expression useful for general coordinates (not just Cartesian) and general spaces (not just Euclidean) takes the form:[60] where gij is called the metric tensor. It may be a function of position. Such curved spaces include Riemannian geometry as a general example. This formulation also applies to a Euclidean space when using curvilinear coordinates. For example, in polar coordinates: Pythagoras' theorem connects two expressions for the magnitude of the cross product. One approach to defining a vector cross product is to require that it satisfies the equation,[61] which involves the dot product. The right-hand side is called the Gram determinant of a and b, and represents the square of the area of the parallelogram formed by these two vectors. From this requirement along with that of orthogonality of the cross product to its constituents a andb, it follows that, apart from the trivial cases of zero and one dimensions, the cross product is defined only in three and seven dimensions.[62]Using the definition of angle in n-dimensions:[63] this property of the cross product provides its magnitude as: Through the fundamental Pythagorean trigonometric identity,[36] another form for the magnitude is found: An alternative approach defines the cross product using this expression for its magnitude. Then reversing the above argument, the connection to the dot product: is derived. There is debate whether the Pythagorean theorem was discovered once, or many times in many places. The history of the theorem can be divided into four parts: knowledge of Pythagorean triples, knowledge of the relationship among the sides of aright triangle, knowledge of the relationships among adjacent angles, and proofs of the theorem within some deductive system. Bartel Leendert van der Waerden conjectured that Pythagorean triples were discovered algebraically by the Babylonians.[64] Written between 2000 and 1786 BC, the Middle Kingdom Egyptian papyrus Berlin 6619 includes a problem whose solution is the Pythagorean triple 6:8:10, but the problem does not mention a triangle. The Mesopotamian tablet Plimpton 322, written between 1790 and 1750 BC during the reign ofHammurabi the Great, contains many entries closely related to Pythagorean triples. In India, the Baudhayana Sulba Sutra, the dates of which are given variously as between the 8th century BC and the 2nd century BC, contains a list of Pythagorean triples discovered algebraically, a statement of the Pythagorean theorem, and a geometrical proof of the Pythagorean theorem for an isosceles right triangle. The Apastamba Sulba Sutra (circa 600 BC) contains a numerical proof of the general Pythagorean theorem, using an area computation. Van der Waerden believes that "it was certainly based on earlier traditions". According to Albert Bŭrk, this is the original proof of the theorem; he further theorizes that Pythagoras visited Arakonam, India, and copied it. Boyer (1991) thinks the elements found in the Śulba-sũtram may be of Mesopotamian derivation.[65] With contents known much earlier, but in surviving texts dating from roughly the first century BC, the Chinese text Zhou Bi Suan Jing (周髀算经), (The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of Heaven) gives an argument for the Pythagorean theorem for the (3, 4, 5) triangle—in China it is called the "Gougu Theorem" (勾股定理).[66][67] During the Han Dynasty, from 202 BC to 220 AD, Pythagorean triples appear in The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art,[68] together with a mention of right triangles.[69] Some believe the theorem arose first in China,[70] where it is alternatively known as the "Shang Gao Theorem" (商高定理),[71] named after the Duke of Zhou's astrologer, and described in the mathematical collection Zhou Bi Suan Jing[72]. Pythagoras, whose dates are commonly given as 569–475 BC, used algebraic methods to construct Pythagorean triples, according toProclus's commentary on Euclid. Proclus, however, wrote between 410 and 485 AD. According to Sir Thomas L. Heath, no specific attribution of the theorem to Pythagoras exists in the surviving Greek literature from the five centuries after Pythagoras lived.[73] However, when authors such as Plutarch and Cicero attributed the theorem to Pythagoras, they did so in a way which suggests that the attribution was widely known and undoubted.[6][74] "Whether this formula is rightly attributed to Pythagoras personally, [...] one can safely assume that it belongs to the very oldest period of Pythagorean mathematics."[33] Around 400 BC, according to Proclus, Plato gave a method for finding Pythagorean triples that combined algebra and geometry. Circa 300 BC, in Euclid's Elements, the oldest extantaxiomatic proof of the theorem is presented.[75] The Pythagorean theorem has arisen in popular culture in a variety of ways.Pythagorean theorem

[edit]Other forms

[edit]Proofs

[edit]Proof using similar triangles

[edit]Euclid's proof

[edit]Proof by rearrangement

[edit]Algebraic proofs

, while the small square has side b − a and area (b − a)2. The area of the large square is therefore

, while the small square has side b − a and area (b − a)2. The area of the large square is therefore

, which is removed by multiplying by two to give the result.

, which is removed by multiplying by two to give the result.[edit]Proof using differentials

,

,

[edit]Converse

[edit]Consequences and uses of the theorem

[edit]Pythagorean triples

[edit]Incommensurable lengths

[edit]Euclidean distance in various coordinate systems

and

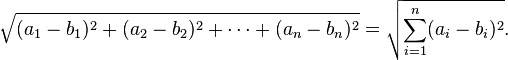

and  , is defined, by generalization of the Pythagorean theorem, as:

, is defined, by generalization of the Pythagorean theorem, as:

The Pythagorean theorem, valid for right triangles, therefore is a special case of the more general law of cosines, valid for arbitrary triangles.

The Pythagorean theorem, valid for right triangles, therefore is a special case of the more general law of cosines, valid for arbitrary triangles.[edit]Pythagorean trigonometric identity

[edit]Generalizations

[edit]Similar figures on the three sides

[edit]Law of cosines

[edit]Arbitrary triangle

[edit]General triangles using parallelograms

[edit]Complex arithmetic

is the complex conjugate of

is the complex conjugate of  . For example, the distance between the points (a, b) = (0, 1) and (c, d) = (i, 0) begins with the difference (a − c, b − d) = (−i, 1) and would work out as 0 if complex conjugates were not taken. Using the modified formula, the result is

. For example, the distance between the points (a, b) = (0, 1) and (c, d) = (i, 0) begins with the difference (a − c, b − d) = (−i, 1) and would work out as 0 if complex conjugates were not taken. Using the modified formula, the result is

[edit]Solid geometry

be orthogonal vectors in ℝn. Consider the n-dimensional simplex S with vertices

be orthogonal vectors in ℝn. Consider the n-dimensional simplex S with vertices  . (Think of the (n−1) dimensional simplex with vertices

. (Think of the (n−1) dimensional simplex with vertices  not including the origin as the "hypotenuse" of S and the remaining (n−1)-dimensional faces of S as its "legs".) Then the square of the volume of the hypotenuse of S is the sum of the squares of the volumes of the n legs.

not including the origin as the "hypotenuse" of S and the remaining (n−1)-dimensional faces of S as its "legs".) Then the square of the volume of the hypotenuse of S is the sum of the squares of the volumes of the n legs.

[edit]Inner product spaces

is zero. The inner product is a generalization of the dot product of vectors. The dot product is called the standardinner product or the Euclidean inner product. However, other inner products are possible.[50]

is zero. The inner product is a generalization of the dot product of vectors. The dot product is called the standardinner product or the Euclidean inner product. However, other inner products are possible.[50]

[edit]Non-Euclidean geometry

[edit]Spherical geometry

![1-left(frac{c}{R}right)^2= left[1-left(frac{a}{R}right)^2 right]left[1-left(frac{b}{R}right)^2 right] + mathrm{higher order terms}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/7/2/8/728048e96e4f839d2e8640f3389c9b5a.png)

[edit]Hyperbolic geometry

[edit]Differential geometry

[edit]Relation to cross product

[edit]History

[edit]Pop references to the Pythagorean theorem

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

(An abbreviated version of this proof is in the second half of Proof #40 at Bogomolny, Alexander. "Pythagorean Theorem". Interactive Mathematics Miscellany and Puzzles. Alexander Bogomolny. Retrieved 2010-05-09.Archived version May 8, 2010.)[edit]References

[edit]External links

|

|

|

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Pythagorean theorem |

19:40 Publié dans Pythagorean theorem | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Conseils de méthode pour l'épreuve de maths

|

|||

|

19:38 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Table of mathematical symbols

This is a listing of common symbols found within all branches of mathematics. Each symbol is listed in both HTML, which depends on appropriate fonts to be installed, and in TEX, as an image. In mathematics written in Arabic, some symbols may be reversed to make right-to-left reading easier. [11] Some Unicode charts of mathematical operators: Some Unicode cross-references:Table of mathematical symbols

Common symbols

See also

Variations

References

External links

Contents[hide] |

| Symbol in HTML | Symbol in TEX | Name | Explanation | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read as | ||||

| Category | ||||

|

is equal to; equals

everywhere

|

x = y means x and y represent the same thing or value. | 2 = 2 1 + 1 = 2 |

|

|

is not equal to; does not equal

everywhere

|

x ≠ y means that x and y do not represent the same thing or value. (The forms !=, /= or <> are generally used in programming languages where ease of typing and use of ASCII text is preferred.) |

2 + 2 ≠ 5 | |

|

is less than, is greater than

|

x < y means x is less than y. x > y means x is greater than y. |

3 < 4 5 > 4 |

|

|

is a proper subgroup of

|

H < G means H is a proper subgroup of G. | 5Z < Z A3 < S3 |

||

|

(very) strict inequality

is much less than, is much greater than

|

x ≪ y means x is much less than y. x ≫ y means x is much greater than y. |

0.003 ≪ 1000000 | |

|

asymptotic comparison

is of smaller order than, is of greater order than

|

f ≪ g means the growth of f is asymptotically bounded by g. (This is I. M. Vinogradov's notation. Another notation is the Big O notation, which looks like f = O(g).) |

x ≪ ex | ||

|

is less than or equal to, is greater than or equal to

|

x ≤ y means x is less than or equal to y. x ≥ y means x is greater than or equal to y. (The forms <= and >= are generally used in programming languages where ease of typing and use of ASCII text is preferred.) |

3 ≤ 4 and 5 ≤ 5 5 ≥ 4 and 5 ≥ 5 |

|

|

is a subgroup of

|

H ≤ G means H is a subgroup of G. | Z ≤ Z A3 ≤ S3 |

||

|

is reducible to

|

A ≤ B means the problem A can be reduced to the problem B. Subscripts can be added to the ≤ to indicate what kind of reduction. | If then |

||

|

≺

|

|

is Karp reducible to; is polynomial-time many-one reducible to

|

L1 ≺ L2 means that the problem L1 is Karp reducible to L2.[1] | If L1 ≺ L2 and L2 ∈ P, then L1 ∈ P. |

|

is proportional to; varies as

everywhere

|

y ∝ x means that y = kx for some constant k. | if y = 2x, then y ∝ x. | |

|

is Karp reducible to; is polynomial-time many-one reducible to

|

A ∝ B means the problem A can be polynomially reduced to the problem B. | If L1 ∝ L2 and L2 ∈ P, then L1 ∈ P. | ||

|

plus; add

|

4 + 6 means the sum of 4 and 6. | 2 + 7 = 9 | |

|

the disjoint union of ... and ...

|

A1 + A2 means the disjoint union of sets A1 and A2. | A1 = {3, 4, 5, 6} ∧ A2 = {7, 8, 9, 10} ⇒ A1 + A2 = {(3,1), (4,1), (5,1), (6,1), (7,2), (8,2), (9,2), (10,2)} |

||

|

minus; take; subtract

|

9 − 4 means the subtraction of 4 from 9. | 8 − 3 = 5 | |

|

negative; minus; the opposite of

|

−3 means the negative of the number 3. | −(−5) = 5 | ||

|

minus; without

|

A − B means the set that contains all the elements of A that are not in B. (∖ can also be used for set-theoretic complement as described below.) |

{1,2,4} − {1,3,4} = {2} | ||

|

times; multiplied by

|

3 × 4 means the multiplication of 3 by 4. (The symbol * is generally used in programming languages, where ease of typing and use of ASCII text is preferred.) |

7 × 8 = 56 | |

|

the Cartesian product of ... and ...; the direct product of ... and ...

|

X×Y means the set of all ordered pairs with the first element of each pair selected from X and the second element selected from Y. | {1,2} × {3,4} = {(1,3),(1,4),(2,3),(2,4)} | ||

|

cross

|

u × v means the cross product of vectors u and v | (1,2,5) × (3,4,−1) = (−22, 16, − 2) |

||

|

the group of units of

|

R× consists of the set of units of the ring R, along with the operation of multiplication. This may also be written R* as described below, or U(R). |

![begin{align} (mathbb{Z} / 5mathbb{Z})^times & = { [1], [2], [3], [4] } \ & cong C_4 \ end{align}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/0/6/f/06f5c6ec9c5a7c6e00e8fd5e18529e9e.png) |

||

|

times; multiplied by

|

3 · 4 means the multiplication of 3 by 4. | 7 · 8 = 56 | |

|

dot

|

u · v means the dot product of vectors u and v | (1,2,5) · (3,4,−1) = 6 | ||

|

divided by; over

|

6 ÷ 3 or 6 ⁄ 3 means the division of 6 by 3. | 2 ÷ 4 = .5 12 ⁄ 4 = 3 |

|

|

mod

|

G / H means the quotient of group G modulo its subgroup H. | {0, a, 2a, b, b+a, b+2a} / {0, b} = {{0, b}, {a, b+a}, {2a, b+2a}} | ||

|

quotient set

mod

|

A/~ means the set of all ~ equivalence classes in A. | If we define ~ by x ~ y ⇔ x − y ∈ ℤ, then ℝ/~ = {x + n : n ∈ ℤ : x ∈ (0,1]} |

||

|

plus or minus

|

6 ± 3 means both 6 + 3 and 6 − 3. | The equation x = 5 ± √4, has two solutions, x = 7 and x = 3. | |

|

plus or minus

|

10 ± 2 or equivalently 10 ± 20% means the range from 10 − 2 to 10 + 2. | If a = 100 ± 1 mm, then a ≥ 99 mm and a ≤ 101 mm. | ||

|

minus or plus

|

6 ± (3 ∓ 5) means both 6 + (3 − 5) and 6 − (3 + 5). | cos(x ± y) = cos(x) cos(y) ∓ sin(x) sin(y). | |

|

the (principal) square root of

|

means the nonnegative number whose square is x. means the nonnegative number whose square is x. |

|

|

|

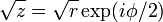

the (complex) square root of

|

if  is represented in polar coordinates with is represented in polar coordinates with  , then , then  . . |

|

||

|

|…|

|

|

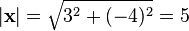

absolute value or modulus

absolute value of; modulus of

|

|x| means the distance along the real line (or across the complex plane) between x and zero. | |3| = 3 |–5| = |5| = 5 | i | = 1 | 3 + 4i | = 5 |

|

Euclidean norm or Euclidean length or magnitude

Euclidean norm of

|

|x| means the (Euclidean) length of vector x. | For x = (3,-4) |

||

|

determinant of

|

|A| means the determinant of the matrix A |  |

||

|

cardinality of; size of; order of

|

|X| means the cardinality of the set X. (# may be used instead as described below.) |

|{3, 5, 7, 9}| = 4. | ||

|

||…||

|

|

norm of; length of

|

|| x || means the norm of the element x of a normed vector space.[3] | || x + y || ≤ || x || + || y || |

|

nearest integer to

|

||x|| means the nearest integer to x. (This may also be written [x], ⌊x⌉, nint(x) or Round(x).) |

||1|| = 1, ||1.6|| = 2, ||−2.4|| = −2, ||3.49|| = 3 | ||

|

divides

|

a|b means a divides b. a∤b means a does not divide b. (This symbol can be difficult to type, and its negation is rare, so a regular but slightly shorter vertical bar | character can be used.) |

Since 15 = 3×5, it is true that 3|15 and 5|15. | |

|

given

|

P(A|B) means the probability of the event a occurring given that boccurs. | if X is a uniformly random day of the year P(X is May 25 | X is in May) = 1/31 | ||

|

restriction of … to …; restricted to

|

f|A means the function f restricted to the set A, that is, it is the function with domain A ∩ dom(f) that agrees with f. | The function f : R → R defined by f(x) = x2 is not injective, but f|R+is injective. | ||

|

such that

such that; so that

everywhere

|

| means “such that”, see ":" (described below). | S = {(x,y) | 0 < y < f(x)} The set of (x,y) such that y is greater than 0 and less than f(x). |

||

|

||

|

|

is parallel to

|

x || y means x is parallel to y. | If l || m and m ⊥ n then l ⊥ n. |

|

is incomparable to

|

x || y means x is incomparable to y. | {1,2} || {2,3} under set containment. | ||

|

exact divisibility

exactly divides

|

pa || n means pa exactly divides n (i.e. pa divides n but pa+1 does not). | 23 || 360. | ||

|

cardinality of; size of; order of

|

#X means the cardinality of the set X. (|…| may be used instead as described above.) |

#{4, 6, 8} = 3 | |

|

connected sum of; knot sum of; knot composition of

|

A#B is the connected sum of the manifolds A and B. If A and Bare knots, then this denotes the knot sum, which has a slightly stronger condition. | A#Sm is homeomorphic to A, for any manifold A, and the sphereSm. | ||

|

aleph

|

ℵα represents an infinite cardinality (specifically, the α-th one, where α is an ordinal). | |ℕ| = ℵ0, which is called aleph-null. | |

|

beth

|

ℶα represents an infinite cardinality (similar to ℵ, but ℶ does not necessarily index all of the numbers indexed by ℵ. ). |  |

|

|

19:34 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Relational Algebra Translator

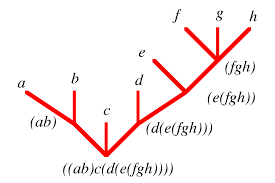

Este software fue desarrollado como proyecto de investigación a cardo del docente M.Sc. Johnny Villalobos Murillo y programado por el estudiante Steven Brenes Chavarría (sbrenesms@gmail.com) de la Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica. El sistema "Relational Algebra Translator (RAT)" cuenta con las siguientes características: Arboles de parser Operadores nuevos (RO, asignación) Mejora en la interfaz Analizador lexicográfico Analizador semántico Generador de arboles de parser Traductor al SQL Conexiones a Sistemas Gestores de Bases de Datos Ejecutar instrucciones SQL

19:30 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | |