21/05/2011

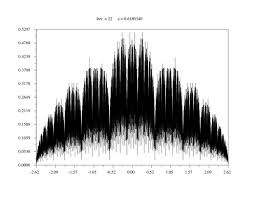

The Structure of Finite Algebras

AMS Titles by Author | AMS Titles by Subject

Source : http://www.ams.org/publications/online-books/conm76-index

|

The Structure of Finite Algebras

David Hobby and Ralph McKenzie Publication Date: 1988 |

|

|

22:28 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Omar Khayyam

Omar Khayyam

| Omar Khayyām | |

|

Omar Khayyām

|

|

| Nom de naissance |

غياث الدین ابو الفتح عمر بن ابراهیم خیام نيشابوری

|

|---|---|

| Activité(s) | Poète ,Mathématicien, philosophe, astronome, |

| Naissance | 18 mai 1048 Nichapur, Perse, Empire seldjoukide |

| Décès | 4 décembre 1131 Nichapur, Perse, Empire seldjoukide |

| Langue d'écriture | persan |

Source : http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omar_Khayyam

L'écrivain et savant persan connu en francophonie sous le nom d'Omar Khayyām1 ou de Khayyām 2 serait né le 18 mai 1048 àNichapur en Perse (actuel Iran) où il est mort le 4 décembre 11313.

On peut aussi trouver son nom orthographié Omar Khayam comme dans les traductions d'Armand Robin (1958) ou de M. F. Farzaneh et Jean Malaplate (dans l'édition critique de Sadegh Hedayat, Corti, 1993).

Sommaire[masquer] |

Biographie[modifier]

La vie de Khayyam est entourée de mystère, et peu de sources sont disponibles pour nous permettre de la retracer avec précision. Les chercheurs pensent généralement qu'Omar Khayyam est né dans une famille d'artisans de Nichapur (son père était probablement fabricant de tentes). Il a passé son enfance dans la ville de Balhi, où il étudie sous la direction du cheik Mohammad Mansuri, un des chercheurs les plus célèbres de son temps. Dans sa jeunesse, Omar Khayyām étudie aussi sous la direction de l'imam Mowaffak de Nishapur, considéré comme le meilleur professeur du Khorassan.

La légende dit qu'Abou-Ali Hassan (Nizam al-Mulk) et Hassan Sabbah étudiaient alors également sous la direction de ce maître et qu'un pacte légendaire aurait été conclu entre les trois étudiants : « Celui d'entre nous qui atteindra la gloire ou la fortune devra partager à égalité avec les deux autres ». Cette alliance reste improbable lorsqu'on sait que Nizam al-Mulk était de 30 ans l'ainé d'Omar et que Hassan Sabbah devait avoir au moins 10 ans de plus que Khayyam.

Nizam al-Mulk devient cependant grand vizir de Perse et les deux autres se rendent à sa cour. Hassan Sabbah, ambitieux, demande une place au gouvernement ; il l'obtient immédiatement et s'en servira plus tard pour essayer de prendre le pouvoir à son bienfaiteur. Il devient après son échec chef des Hashishins. Khayyam, moins porté vers le pouvoir politique, ne demande pas de poste officiel, mais un endroit pour vivre, étudier la science et prier. Il reçoit alors une pension de 1 200 mithkals d'or de la part du trésor royal ; cette pension lui sera versée jusqu'à la mort de Nizam al-Mulk (tué par un assassin).

Nom de Khayyam[modifier]

Si on le déchiffre avec le système abjad, le résultat donne al-Ghaqi, le dissipateur de biens, expression qui dans la terminologie soufie est attribuée à "celui qui distribue ou ignore les biens du monde constituant un fardeau dans le voyage qu'il entreprend sur le sentier soufi" (Omar Ali-Shah) [réf. nécessaire].

« Khayyam, qui cousait les tentes de l'intelligence,

Dans une forge de souffrances tomba, subitement brûla;

Des ciseaux coupèrent les attaches de la tente de sa vie;

Le brocanteur de destins le mit en vente contre du vent4. »

Mathématicien et astronome[modifier]

|

|

Des sources utilisées dans cet article ou section sont obsolètes ou trop anciennes.

Améliorez sa pertinence en améliorant ses sources.

|

Omar Khayyâm est considéré comme « l'un des plus grands mathématiciens du Moyen âge5. » Mais ses travaux algébriques ne furent connus6 en Europe qu'au xixe siècle 7.

Dans ses Démonstrations de problèmes d'algèbre de 1070, Khayyam démontre que les équations cubiques peuvent avoir plus d’une racine. Il fait état aussi d’équations ayant deux solutions, mais n'en trouve pas à trois solutions. C'est le premier mathématicien qui ait traité systématiquement des équations cubiques, en employant d'ailleurs des tracés de coniques pour déterminer le nombre des racines réelles et les évaluer approximativement. Outre son traité d'algèbre, Omar Khayyâm a écrit plusieurs textes sur l'extraction des racines cubiques et sur certaines définitions d'Euclide, et a construit des tables astronomiques connues sous le nom de Zidj-e Malikshahi

Directeur de l'observatoire d'Ispahan en 1074, il réforme, à la demande du sultan Malik Shah, le calendrier persan (la réforme est connue sous le nom de réforme jelaléenne). Il introduit une année bissextile et mesure la longueur de l’année comme étant de 365,24219858156 jours. Or la longueur de l’année change à la sixième décimale pendant une vie humaine. L'estimation djélaléenne se montrera plus exacte que la grégorienne créée cinq siècles plus tard, bien que leur résultat pratique soit exactement le même, une année devant comporter un nombre entier de jours. À la fin du xixe siècle, l'année fait 365,242196 jours et aujourd’hui 365,242190 jours.

Poète et philosophe[modifier]

Ses poèmes sont appelés « rubaiyat » (persan: رباعى [rabāʿi], pluriel رباعیات [rubāʿiyāt]8), ce qui signifie « quatrains ». Les quatrains de Khayyam, souvent cités en Occident pour leur scepticisme, recèleraient, selon Idries Shah, des "perles mystiques", faisant de Khayyam un soufi. Il aurait prôné l'ivresse de Dieu, et se disait infidèle mais croyant9. Au-delà du premier degré hédoniste, les quatrains auraient donc selon ce commentateur une dimension mystique.

Dans la pratique, si l'on s'en tient au texte, Khayyam se montre bel et bien fort critique vis-à-vis des religieux - et de la religion - de son temps. Quant au vin dont la mention revient fréquemment dans ses quatrains, le contexte où il se place constamment (agréable compagnie de jeunes femmes ou d'échansons, refus de poursuivre la recherche de cette connaissance que Khayyam a jadis tant aimée) ne lui laisse guère de latitude pour être allégorique.

On ne peut donc que constater l'existence de ces deux points de vue. Traduction de F. Toussaint pour les quatrains ci-après.

- Chagrin et désespoir

(VIII)

« En ce monde, contente-toi d'avoir peu d'amis.

Ne cherche pas à rendre durable

la sympathie que tu peux éprouver pour quelqu'un.

Avant de prendre la main d'un homme,

demande-toi si elle ne te frappera pas, un jour. »

(CXX)

« Tu peux sonder la nuit qui nous entoure.

Tu peux foncer sur cette nuit... Tu n'en sortiras pas.

Adam et Ève, qu'il a dû être atroce, votre premier baiser,

puisque vous nous avez créés désespérés ! »

- Lucidité et scepticisme

(CXLI)

« Contente-toi de savoir que tout est mystère :

la création du monde et la tienne,

la destinée du monde et la tienne.

Souris à ces mystères comme à un danger que tu mépriserais. »

« Ne crois pas que tu sauras quelque chose

quand tu auras franchi la porte de la Mort.

Paix à l'homme dans le noir silence de l'Au-Delà ! »

- Sagesse et épicurisme

(XXV)

« Au printemps, je vais quelquefois m'asseoir à la lisière d'un champ fleuri.

Lorsqu'une belle jeune fille m'apporte une coupe de vin, je ne pense guère à mon salut.

Si j'avais cette préoccupation, je vaudrais moins qu'un chien. »

(CLXX)

« Luths, parfums et coupes,

lèvres, chevelures et longs yeux,

jouets que le Temps détruit, jouets !

Austérité, solitude et labeur,

méditation, prière et renoncement,

cendres que le Temps écrase, cendres ! »

C'est sur cette 170e pièce, comme en conclusion de ce qui précède, que se termine le recueil.

- Distance par rapport à l'islam orthodoxe

(CVII)

« Autrefois, quand je fréquentais les mosquées,

je n'y prononçais aucune prière,

mais j'en revenais riche d'espoir.

Je vais toujours m'asseoir dans les mosquées,

où l'ombre est propice au sommeil. »

(CLIX)

« “ Allah est grand !” . Ce cri du moueddin ressemble à une immense plainte.

Cinq fois par jour, est-ce la Terre qui gémit vers son créateur indifférent ? »

(CLIII)

« Puisque notre sort, ici-bas, est de souffrir puis de mourir,

ne devons-nous pas souhaiter de rendre le plus tôt possible à la terre notre corps misérable ?

Et notre âme, qu'Allah attend pour la juger selon ses mérites, dites-vous ?

Je vous répondrai là-dessus quand j'aurai été renseigné par quelqu'un revenant de chez les morts. »

Notoriété universelle et image ambiguë[modifier]

Des agnostiques occidentaux voient en lui un de leurs frères né trop tôt, tandis que certains musulmans perçoivent plutôt chez lui un symbolismeésotérique, rattaché au soufisme.

Khayyam indiquerait, comme le fera Djalâl ad-Dîn Rûmî plus tard, que l'homme sur le chemin de Dieu n'a pas besoin de lieu dédié pour vénérer son Dieu, et que la fréquentation des sanctuaires religieux n'est ni une garantie du contact avec Dieu, ni un indicateur du respect d'une discipline intérieure.

L'actuelle république islamique d'Iran ne nie pas les positions de Khayyam, mais a fait paraître au début des années 80 une liste officielle des quatrains qu'elle considérait comme authentiques (comme pour les Pensées de Pascal, leur nombre et leur numérotation diffèrent selon les compilateurs).

La vision d'un Khayyam ésotériste n'est pas partagée par ceux qui voient en lui surtout un hédoniste tolérant et sceptique. En effet, si certains[réf. souhaitée]assimilent dans ses poèmes le vin à une sorte de manne céleste, d'autres comme Sadegh Hedayat considèrent plutôt le poète comme un chantre de la liberté individuelle, qui refuse de trancher sur des mystères lui semblant hors de portée de l'homme. Son appréciation simple des plaisirs terrestres après la quadruple déception de la religion (quatrains 25, 76, 141), des hommes (quatrains 8, 18, 33) de la science (quatrains 26 à 30, 77, 81) et de la condition humaine elle-même (quatrains 32, 67, 107, 120, 170) n'exclut aucune hypothèse (quatrains 1, 23 à 25, 52)10.

Si chacune des deux interprétations est controversée par les tenants de l'autre, elles ne s'excluent cependant pas nécessairement : Khayyam présentesans ordre et sans méthode, pour reprendre une expression de Montaigne dans la préface des Essais - donc sans stratégie visant à convaincre - ses espoirs, ses doutes et ses découragements dans ce qui semble un effort de vérité humaine. C'est peut-être une des raisons du succès mondial des quatrains.

Traductions[modifier]

Controverses autour des manuscrits et des traductions[modifier]

- La diversité des manuscrits, et leur authenticité, ainsi que la connaissance de la langue et de la Perse du onzième siècle montrent les difficultés d'une traduction. Marguerite Yourcenar dit à ce propos : « Quoi qu'on fasse, on reconstruit toujours le monument à sa manière. Mais c'est déjà beaucoup de n'employer que des pierres authentiques »11. Armand Robin dresse une liste de ces pierres dans Ce qu'en 1958 on peut savoir sur les « quatrains » d'Omar Khayam lors de sa traduction (cf. Bibliographie).

- Manuscrit de 1460 de la "Bodleian Library" d'Oxford, soit 158 quatrains traduits, en anglais par Fitzgerald (1859), en français par Charles Grolleau (1909). Une centaine de ces quatrains sont incertains.

- Manuscrit de 464 quatrains traduits en français par J.-B. Nicolas (1861).

- Manuscrit d'Istanbul, 375 quatrains étudiés fin XIXe début xxe siècle

- Manuscrit de Lucknow, 845 quatrains étudiés fin XIXe début xxe siècle

- Manuscrit de 1259 dit de "Chester-Beatty", du scribe Mohammed al Qâwim de Nichapour, 172 quatrains traduits en français par Vincent Monteil (1983).

- Manuscrit de 1207 dit de "Cambridge", acheté en 1950. Anthologie de 250 quatrains traduits par le professeur Arthur J. Arberry (1952, il avait expertisé le manuscrit "Chester-Beatty".

- Manuscrit de 1153 découvert "dans une immense bibliothèque familiale", 111 quatrains traduits en anglais par Omar Ali-Shah "de langue maternelle persane, soufi..." (1964).

- Traductions et interprétations.

Le fait que les rubaiyat soient un recueil de quatrains - qui peuvent être sélectionnés et réarrangés subjectivement afin de démontrer une interprétation ou une autre - a mené à des versions qui diffèrent grandement. J.-B. Nicolas12 a pris le parti de dire que Khayyam se considère clairement comme un soufi. D'autres y ont vu des signes de mysticisme, ou même d'athéisme, et d'autres au contraire le signe d'un Islam dévot et orthodoxe. Fitzgerald a donné au Rubaiyat une atmosphère fataliste, mais s'il est dit qu'il a adouci l'impact du nihilisme de Khayyam et de ses préoccupations de la mort et du caractère transitoire de toutes choses. La question de savoir si Khayyam était pour ou contre la consommation de vin serait même pour certains controversée 13!

Dans la nouvelle traduction que Jean-Yves Lacroix (Le cure-dent, éd.Allias) fait des quatrains "Rubaï'yat" du grand persan, qualifiés de "serpent venimeux pour la loi divine", par le chroniqueur al-Qifti, Khayyam écrit : "Tout le monde sait que je n'ai jamais murmuré la moindre prière", et ailleurs ceci : "Referme ton Coran. Pense librement et regarde librement le ciel et la terre."

Les quatrains de Khayyâm font l'objet de quelques controverses de traduction ainsi que d'éditions. En Europe, Fitzgerald et Toussaint sont les références les plus courantes. Il est cependant difficile, comme dans toute traduction poétique, de rendre tout le sens original des vers. Le sens mystique de cette poésie peut échapper au non-spécialiste. Quant à Fitzgerald, il combine parfois des quatrains distincts pour rendre possible une rime (Toussaint, mécontent de la traduction de Fitzgerald, préfère une prose à laquelle il donne un soufflepoétique).

Le contenu original du recueil de quatrains de Kayyâm est aussi soumis à de vastes débats. En effet, la tradition attribue plus de 1000 quatrains à Khayyam; alors que la plupart des chercheurs ne lui en attribuent avec certitude que 50, avec environ 200 autres quatrains soumis à controverse14. Chez Toussaint et Fitzgerald, le nombre est de 170.

Le gouvernement iranien a fait paraître dans les années 1980 la liste des quatrains qu'il reconnait officiellement.

Découverte d'Omar Khayyâm en Occident suite aux traductions d'Edward Fitzgerald[modifier]

Ce fut la traduction anglaise d'Edward FitzGerald qui fit connaître au grand public, en 1859, l'œuvre poétique de Khayyam et qui servit de référence aux traductions dans beaucoup d'autres langues.

Fitzgerald dut effectuer un choix parmi les mille poèmes attribués à Khayyam par la tradition, car le genre littéraire qu'il avait inauguré avait connu un tel succès que l'on employait le terme générique khayyam pour désigner toute lamentation désabusée sur la condition humaine. Fitzgerald établit quatre éditions des quatrains comprenant entre 75 et 110 quatrains. Étonnamment, c'est encore souvent une des compilations établies par Fitzgerald qui sert de référence à une grande partie des autres traductions.

Les traductions de Fitzgerald sont encore très discutées, notamment dans ce qui concerne leur authenticité, Fitzgerald ayant profité de ces traductions pour réécrire totalement des passages hors de l'esprit du poète original, comme la plupart des traducteurs de l'époque le faisaient. Ainsi, Omar Ali-Shah prend l'exemple du premier quatrain afin de montrer les étonnantes divergences de sens entre la traduction anglaise et la traduction littérale française.

| Texte persan en caractères latins | Traduction anglaise de Fitzgerald | Traduction française d'après Fitzgerald |

|---|---|---|

| I. Khurshid kamândi sobh bar bâm afgand |

I. Awake ! for Morning in the Bowl of Night |

I. Réveille-toi ! Car le matin, dans le bol de la nuit, |

| Texte persan en caractères latins | Traduction française du texte anglais d'Omar Ali-Shah | |

| I. Khurshid kamândi sobh bar bâm afgand |

I. Tandis que l'Aube, héraut du jour chevauchant tout le ciel, |

Traduction du persan en français de l'orientaliste Franz Toussaint[modifier]

L'orientaliste français Franz Toussaint préféra effectuer une nouvelle traduction à partir du texte original persan plutôt qu'à partir de l'anglais, avec le parti-pris de ne pas chercher à traduire les quatrains en quatrains, mais dans une prose poétique qu'il estimait plus fidèle. Sa traduction française, composée de 170 quatrains, a été contestée par les uns, défendue par d'autres avec vigueur. Aujourd'hui, après la disparition des Éditions d'art Henri Piazza qui l'ont largement diffusée entre 1924 et 1979, cette traduction fait elle-même l'objet de traductions dans d'autres langues. Toussaint, décédé en 1955, n'a pas été témoin de ce succès.

Dilemme des traducteurs[modifier]

Quelques quatrains semblent échapper à toute traduction définitive, en raison de la complexité de la langue persane. Ainsi, Khayyam mentionne un certain Bahram (probablementVahram V Gour) qui de son vivant prenait grand plaisir à attraper des onagres (Bahram ke Gour migerefti hame 'omr) et ajoute laconiquement que c'est la tombe qui a attrapé Bahram. Les mots onagre et tombe sont phonétiquement voisins en farsi, avec une phonie ressemblant à gour (Didi keh chegune gour bahram gereft).

L'édition récente de la traduction française des quatrains par Omar Ali-Shah critique la plupart des traductions antérieures, à commencer par celle de Fitzgerald ou certaines[réf. souhaitée]traductions françaises. Selon Omar Ali-Shah, le persan des quatrains de Khayyâm se réfère constamment au vocabulaire soufi et a été injustement traduit dans l'oubli de sa signification spirituelle. Ainsi il affirme que le "Vin" de Khayyâm est un vin spirituel, que la Tariqa est la Voie (sous entendue au sens soufi de chemin mystique vers Dieu) et non la "route" ou "route secondaire", présente selon lui dans certaines traductions (il ne précise pas lesquelles). Néanmoins les quatrains laissant paraître un scepticisme désabusé ne trouvent dans cette optique aucune explication.

On ne sait si la traduction effectuée par l'Imprimerie nationale est fidèle, mais elle ne contient pour sa part pas de métrique qui suggère (ou "rende") l'effet d'un travail poétique.

Quelques quatrains[modifier]

« Hier est passé, n’y pensons plus

Demain n’est pas là, n’y pensons plus

Pensons aux doux moments de la vie

Ce qui n’est plus, n’y pensons plus »

« Ce vase était le pauvre amant d’une bien-aimée

Il fut piégé par les cheveux d’une bien-aimée

L’anse que tu vois, au cou de ce vase

Fut le bras autour du cou d’une bien-aimée! »

« Elle passe bien vite cette caravane de notre vie

Ne perds rien des doux moments de notre vie

Ne pense pas au lendemain de cette nuit

Prends du vin, il faut saisir les doux moments de notre vie »

— Dictionnaire des poètes renommés persans: A partir de l'apparition du persan dari jusqu'à nos jours, Téhéran, Aryan-Tarjoman, 2007.

Khayyâm l'inspirateur[modifier]

Omar Khayyâm, depuis sa découverte en Occident, a exercé une fascination récurrente sur des écrivains européens comme par exemple Marguerite Yourcenar, qui confessait "une autre figure historique (que celle de l'empereur Hadrien) m'a tentée avec une insistance presque égale: Omar Khayyam... Mais (sa) vie... est celle du contemplateur, et du contempteur pur" tout en ajoutant, avec une humilité qui fait défaut à beaucoup de "traducteurs", "D'ailleurs, je ne connais pas la Perse et n'en sais pas la langue"15.

Il inspira aussi le roman Samarcande d'Amin Maalouf.

Musicalement, il inspira également les compositeurs suivants :

- sir Granville Bantock : Omar Khayyam, grande symphonie pour solistes, chœurs et orchestre

- Jean Cras : Roubayat, cycle de mélodies

- Sofia Goubaïdoulina : Roubayat, cycle de mélodies.

Divers[modifier]

- Un cratère lunaire a été baptisé de son nom en 1970.

- L'astéroïde 3095 Omarkhayyam a été nommé en son honneur en 1980.

Bibliographie[modifier]

Oeuvres poétiques[modifier]

- L'amour, le désir, & le vin. Omar Khâyyâm (60 poèmes sur l'Amour et le Vin). Calligraphies de Lassaad Métoui. Paris, Alternatives, 2008, 128p.

- Les Quatrains d'Omar Khâyyâm, traduits du Persan et présentés par Charles Grolleau, Ed. Charles Corrington, 1902. (Rééd. éditions Champ libre / Ivrea, 1978). (Rééd. éditions 1001 Nuits, 79p., 1995). (Rééd. éditions Allia, 2008).

- Rubayat Omar Khayam, traduction d'Armand Robin (1958), (Rééd. Préf. d'André Velter, Poésie/Gallimard, 109p., 1994, ISBN : 207032785X ).

- "Quatrains Omar Khayyâm suivi de Ballades Hâfez", Poèmes choisis, traduits et présentés par Vincent Monteil, bilingue Calligraphies de Blandine Furet, 171p., Coll. La Bibliothèque persane, Ed. Sindbad, 1983.

- Les Chants d'Omar Khayyâm, édition critique, traduits du Persan par M. F. Farzaneh et Jean Malaplate, Éditions José Corti, 1993.

- Les Chants d'Omar Khayam, traduits du Persan par Sadegh Hedayat, Éditions José Corti, 1993.

- Quatrains d'Omar Khayyâm, édition bilingue, poèmes traduits du persan par Vincent-Mansour Monteil, Éditions Actes Sud, Collection Babel, 1998. ISBN : 2-7427-4744-3.

- Cent un quatrain de libre pensée d'Omar Khayyâm, édition bilingue, traduit du persan par Gilbert Lazard, Éditions Gallimard, Connaissance de l'Orient, 2002. ISBN : 978-2-07-076720-5.

- Les quatrains d'Omar Khayyâm, traduction du persan & préf. d'Omar Ali-Shah, trad. de l'anglais par Patrice Ricord, Coll. Spiritualités vivantes, Albin Michel, 146p., 2005, ISBN : 2226159134.

Oeuvres mathématiques[modifier]

Voir aussi la bibliographie des Irem (France).

- Traité sur l'algèbre (vers 1070). Voir Roshid Rashed et Ahmed Djebbar, L'oeuvre algébrique d'al-Khayyâm, Alep, 1981.

A la fin de l'an 1077, il achève son commentaire sur certaines prémisses problématiques du Livre d'Euclide, en trois chapitres.

Études sur Khayyâm poète[modifier]

Études sur Khayyâm mathématicien[modifier]

- R. Rashed, Al-Khayyam mathématicien, en collaboration avec B. Vahabzadeh, Paris, Librairie Blanchard, 1999, 438 p. Version anglaise : Omar Khayyam. The Mathematician, Persian Heritage Series n° 40, New York, Bibliotheca Persica Press, 2000, 268 p. (sans les textes arabes).

- R. Rashed, L’Œuvre algébrique d'al-Khayyam (en collaboration avec A. Djebbar), Alep : Presses de l’Université d’Alep,1981, 336 p.

- A. Djebbar, L'émergence du concept de nombre réel positif dans l'Épître d'al-Khayyâm (1048-1131)

Approches romanesques de Khayyâm[modifier]

- Amin Maalouf évoque Omar Khayyâm ainsi que Nizam al-Mulk et Hassan ibn al-Sabbah dans son roman Samarcande (1988).

- Omar Khayyâm apparaît également en filigrane dans le roman de Vladimir Bartol Alamut, compagnon de jeunesse de Hassan ibn al-Sabbah, le fondateur de la secte des Assassins.

- Mehdi Aminrazavi, The Wine of Wisdom - The Life, Poetry and Philosophy of Omar Khayyam, Oneworld Oxford 2005.

- Jacques Attali dans son roman "La confrérie des éveillés" (2005) fait référence à Omar Khayyâm

- Linda Lê dans son roman "Les Trois Parques" (éd Christian Bourgois, 1997) le cite à plusieurs reprises

- Marjane Satrapi cite un poème de Khayyâm dans la bande dessinée Poulet aux prunes

- Denis Guedj dans son roman retraçant l'histoire des mathématiques Le Théorème du Perroquet

- Jean-Yves Lacroix qui nous livre une biographie romancée d'Omar Khayyâm Le Cure-Dent (ISBN : 978-2-84485-283-0)

- Xavier Philiponet dans le récit "Le troisième oeil", Les Joueurs d'Astres (avril 2010 - ISBN : 978-2-9531182-1-6), consacre un chapitre entier à Omar Khayyâm et à Samarcande.

- Dans son ouvrage Le loup des mers, Jack London fait connaitre Omar Khayyâm au capitaine Loup Larsen par le narrateur. 3 jours durant, Humphrey récite les quatrains de Khayyâm à Larsen.

- (ar) Rubayyat Al-Khayam : oeuvre du poète égyptien Ahmed Rami

Notes et références[modifier]

- Ghiyath ed-din Abdoul Fath Omar Ibn Ibrahim al-Khayyām Nishabouri, (persan : غياث الدين ابو الفتح عمر بن ابراهيم خيام نيشابوري [ḡīyāṯ ad-dīn abū al-fatḥ ʿumar ben ibrāhīm ḫayām nīšābūrī])

- (du persan: خيام [ḫayām], en arabe : خَيَّميّ [ḫayyamī] : fabricant de tentes)

- Samarcande, par Amin Maalouf [archive]. La date de 1123 est parfois donnée.

- Omar Khayyam, Rubayat, Poésie/Gallimard

- G. Sarton, Introduction to the History of Science, Washington, 1927[réf. incomplète]

- Franck Woepcke L'algèbre d'Omar Alkhayyämi, publiée, traduite et accompagnée de manuscrits inédits, 51 + 127p. Paris, 1851. Lire l'ouvrage sur Gallica [archive][réf. incomplète]

- Armand Robin, Un algébriste lyrique, Omar Khayam, in La Gazette Littéraire de Lausanne, les 13 & 14 décembre 1958.

- De l'arabe رباعية [rubāʿīya], pluriel رباعيات [rubāʿiyāt] ; « quatrains » (c.f. Steingass, Francis Joseph, A Comprehensive Persian-English dictionary..., London, Routledge & K. Paul, 1892 [lire en ligne [archive]], p. 0567). Le rythme des vers 1, 2 et 4 de chaque quatrain doivent en principe être sur le modèle « ¯ ¯ ˘ ˘ ¯ ¯ ˘ ˘ ¯ ¯ ˘ ˘ ¯ », (son bref : ˘ ; long : ¯) (c.f. Hayyim, Sulayman, New Persian-English dictionary..., vol. 1, Teheran, Librairie-imprimerie Beroukhim, 1934-1936 [lire en ligne [archive]], p. 920). Le nombre 4 se dit ʾarbaʿa, أربعة et dérive de rubʿ, ربع, « le quart » en arabe et se dit šahār, چﮩار en persan.

- Il écrit cependant : Sur la Terre bariolée, chemine quelqu'un qui n'est ni musulman ni infidèle, ni riche, ni humble. / Il ne révère ni Dieu, ni les lois. / Il ne croit pas à la vérité, il n'affirme jamais rien. / Sur la Terre bariolée, quel est cet homme brave et triste ? (Roubaïat 108, Toussaint)

- Les numéros se réfèrent à la traduction de Toussaint

- Carnets de notes de "Mémoires d'Hadrien", Folio Gallimard, impr de 2007, p.342 .

- consul de France à Recht, interprète à la légation de France à Téhéran, traduction en 1861 des quatrains d'après un manuscrit comportant 464 quatrains

- "Pourquoi ne pas en faire un Leibnitz écrivant de temps en temps des billets doux et de tout petits poèmes sur le coin d'une table, quand il en avait assez de tout ce qu'il avait dans le cerveau" Armand Robin in Traduction p.105, cf Bibliographie

- "Omar Khayyam" [archive], Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Carnets de notes de "Mémoires d'Hadrien", p.329, Folio/Gallimard, impr. 2007

Lien externe[modifier]

- Portail du monde arabo-musulman

- Portail de l’Iran

- Portail de l’astronomie

- Portail des mathématiques

- Portail de la poésie

22:24 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Al-Khawarizmi

Al-Khawarizmi

|

|

Cette page contient des caractères spéciaux.

Si certains caractères de cet article s’affichent mal (carrés vides, points d’interrogation, etc.), consultez la page d’aide Unicode.

|

Al-Khawarizmi1, né vers 783, originaire de Khiva dans la région du Khwarezm2 qui lui a donné son nom, mort vers 850 à Bagdad, est un mathématicien, géographe, astrologue etastronome musulman perse dont les écrits, rédigés en langue arabe, ont permis l'introduction de l'algèbre en Europe3. Sa vie s'est déroulée en totalité à l'époque de la dynastieAbbasside. Il est à l'origine des mots « algorithme » (qui n'est autre que son nom latinisé: "algoritmi" 3) et « algèbre » (issu d'une méthode et du titre d'un de ses ouvrages) ou encore de l'utilisation des chiffres arabes dont la diffusion dans le Moyen-Orient et en Europe provient d'un autre de ses livres (qui lui-même traite des mathématiques indiennes).

Son apport en mathématiques fut tel qu'il est également surnommé « le père de l'algèbre », avec Diophante d'Alexandrie, dont il reprendra les travaux. En effet, il fut le premier à répertorier de façon systématique des méthodes de résolution d'équations en classant celles-ci.

Il ne faut pas confondre ce mathématicien arabo-musulman avec un autre mathématicien perse : Abu-'Abdollâh Mohammad Khuwârizmi (en) qui, lui, est l'auteur de Mafâtih al-'Olum(ouvrage de mathématiques écrit vers 976).

Un cratère de la Lune a été nommé en son honneur : le cratère Al-Khwarizmi.

Sommaire[masquer] |

Apports[modifier]

Il n'inventa pas les algorithmes (le plus ancien algorithme alors connu était celui d'Euclide, et on en découvrira au XXe siècle dans les anciennes tablettes de Babylone, servant au calcul de l'impôt), mais il en formalise la théorie en regroupant leurs points communs, en particulier la nécessité d'un critère d'arrêt.

En mathématiques[modifier]

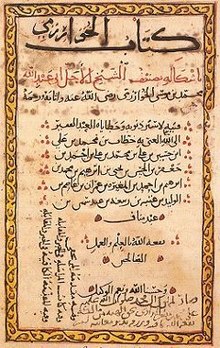

Il est l'auteur de plusieurs ouvrages de mathématiques dont l'un des plus célèbres est intitulé kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wa'l-muqābalah (كتاب المختصر في حساب الجبر والمقابلة), ou Abrégé du calcul par la restauration et la comparaison, publié en 825. Ce livre contient six chapitres, consacrés chacun à un type particulier d'équation. Il ne contient aucun chiffre. Toutes les équations sont exprimées avec des mots. Le carré de l'inconnue est nommé « le carré » ou mâl, l'inconnue est « la chose » ou shay (šay) ou jidhr, la constante est le dirham ou adǎd. Le terme al-jabr4 fut repris par les Européens et devint plus tard le mot algèbre.

Un autre ouvrage, qui ne nous est pas parvenu, Kitāb 'al-ĵāmi` wa'l-tafrīq bī h'isāb ’al-Hind (كتاب الجامع و التفريق بحساب الهند, « Livre de l'addition et de la soustraction d'après le calcul indien »), qui décrit le système des chiffres « arabes » (en fait, empruntés aux Indiens), fut le vecteur de la diffusion de ces chiffres dans le Moyen-Orient et dans le Califat de Cordoue, d'où Gerbert d'Aurillac (Sylvestre II) les fera parvenir au monde chrétien5.

En astronomie[modifier]

Al-Khawarizmi est l'auteur d'un zij, paru en 820, et connu sous le nom de Zīj al-Sindhind (Table indienne).

Le principe des algorithmes était connu depuis l'Antiquité (algorithme d'Euclide), et Donald Knuth mentionne même leur usage par les Babyloniens.

Notes et références[modifier]

- ou Al-Khuwarizmi dont le nom entier est en persan : Abû Ja`far Muhammad ben Mūsā Khwārezmī ابوجعفر محمد بن موسی خوارزمی ou Abû `Abd Allah Muhammad ben Mūsā al-Khawārizmī (arabe أبو عبد الله محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي , également orthographié comme Abu Abudllah Muhammad bin Musa al-Khwarizmi ou Al-Khorezmi)

- On ignore s'il est né à Khiva puis a émigré à Bagdad ou si ce sont ses parents qui ont émigré ; auquel cas il pourrait être né à Bagdad.

- Encyclopédia Britannica, al-Khwarizmi [archive].

- Al-jabr est resté avec son sens originel de restauration / remise en place dans le mot espagnol algebrista qui désigne un « rebouteux » qui remet en place les articulations et les os démis. Voir (es) algebrista (2) [archive] sur Diccionario de la lengua española

- Voir André Allard (éd. sc.), Muhammad Ibn Mūsā Al-Khwārizmī. Le calcul indien (algorismus), Librairie scientifique et technique A. Blanchard, Paris ; Société des Études classiques, Namur, 1992.(ISBN 978-2-87037-174-9)

Voir aussi[modifier]

Liens internes[modifier]

Liens externes[modifier]

- (fr) Ressources et bibliographie sur le site de la Commission inter-Instituts de recherche sur l’enseignement des mathématiques (inter-IREM) "Épistémologie et histoire des mathématiques" (av. 2007).

- (en) John J. O'Connor et Edmund F. Robertson, « Al-Khawarizmi », MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, université de St Andrews.

- Portail du monde arabo-musulman

- Portail de l’Iran

- Portail de l'Ouzbékistan

- Portail des mathématiques

22:23 | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Addition

Addition

Addition is a mathematical operation that represents combining collections of objects together into a larger collection. It is signified by the plus sign (+). For example, in the picture on the right, there are 3 + 2 apples—meaning three apples and two other apples—which is the same as five apples. Therefore, 3 + 2 = 5. Besides counting fruits, addition can also represent combining other physical and abstract quantities using different kinds of numbers: negative numbers,fractions, irrational numbers, vectors, decimals and more.

Addition follows several important patterns. It is commutative, meaning that order does not matter, and it is associative, meaning that when one adds more than two numbers, order in which addition is performed does not matter (see Summation). Repeated addition of 1 is the same as counting; addition of 0 does not change a number. Addition also obeys predictable rules concerning related operations such as subtraction and multiplication. All of these rules can be proven, starting with the addition of natural numbers and generalizing up through the real numbers and beyond. General binary operations that continue these patterns are studied in abstract algebra.

Performing addition is one of the simplest numerical tasks. Addition of very small numbers is accessible to toddlers; the most basic task, 1 + 1, can be performed by infants as young as five months and even some animals. In primary education, children learn to add numbers in the decimal system, starting with single digits and progressively tackling more difficult problems. Mechanical aids range from the ancient abacus to the modern computer, where research on the most efficient implementations of addition continues to this day.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Notation and terminology

Addition is written using the plus sign "+" between the terms; that is, in infix notation. The result is expressed with an equals sign. For example,

- 1 + 1 = 2 (verbally, "one plus one is equal to two")

- 2 + 2 = 4 (verbally, "two plus two is equal to four")

- 5 + 4 + 2 = 11 (see "associativity" below)

- 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 = 12 (see "multiplication" below)

There are also situations where addition is "understood" even though no symbol appears:

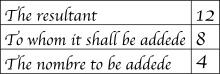

- A column of numbers, with the last number in the column underlined, usually indicates that the numbers in the column are to be added, with the sum written below the underlined number.

- A whole number followed immediately by a fraction indicates the sum of the two, called a mixed number.[2] For example,

3½ = 3 + ½ = 3.5.

This notation can cause confusion since in most other contexts juxtaposition denotes multiplication instead.

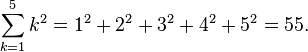

The sum of a series of related numbers can be expressed through capital sigma notation, which compactly denotes iteration. For example,

The numbers or the objects to be added in general addition are called the "terms", the "addends", or the "summands"; this terminology carries over to the summation of multiple terms. This is to be distinguished from factors, which are multiplied. Some authors call the first addend theaugend. In fact, during the Renaissance, many authors did not consider the first addend an "addend" at all. Today, due to the symmetry of addition, "augend" is rarely used, and both terms are generally called addends.[3]

All of this terminology derives from Latin. "Addition" and "add" are English words derived from the Latin verb addere, which is in turn acompound of ad "to" and dare "to give", from the Proto-Indo-European root *deh₃- "to give"; thus to add is to give to.[3] Using the gerundivesuffix -nd results in "addend", "thing to be added".[4] Likewise from augere "to increase", one gets "augend", "thing to be increased".

"Sum" and "summand" derive from the Latin noun summa "the highest, the top" and associated verbsummare. This is appropriate not only because the sum of two positive numbers is greater than either, but because it was once common to add upward, contrary to the modern practice of adding downward, so that a sum was literally higher than the addends.[6] Addere and summare date back at least to Boethius, if not to earlier Roman writers such as Vitruvius and Frontinus; Boethius also used several other terms for the addition operation. The later Middle English terms "adden" and "adding" were popularized by Chaucer.[7]

[edit]Interpretations

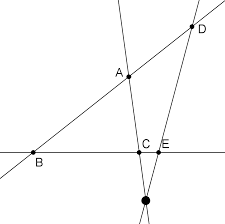

Addition is used to model countless physical processes. Even for the simple case of adding natural numbers, there are many possible interpretations and even more visual representations.

[edit]Combining sets

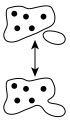

Possibly the most fundamental interpretation of addition lies in combining sets:

- When two or more disjoint collections are combined into a single collection, the number of objects in the single collection is the sum of the number of objects in the original collections.

This interpretation is easy to visualize, with little danger of ambiguity. It is also useful in higher mathematics; for the rigorous definition it inspires, seeNatural numbers below. However, it is not obvious how one should extend this version of addition to include fractional numbers or negative numbers.[8]

One possible fix is to consider collections of objects that can be easily divided, such as pies or, still better, segmented rods.[9] Rather than just combining collections of segments, rods can be joined end-to-end, which illustrates another conception of addition: adding not the rods but the lengths of the rods.

[edit]Extending a length

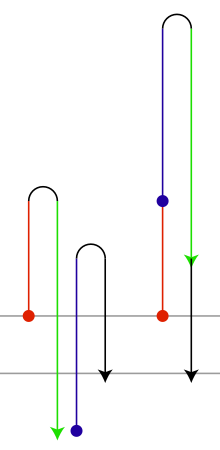

A second interpretation of addition comes from extending an initial length by a given length:

- When an original length is extended by a given amount, the final length is the sum of the original length and the length of the extension.

The sum a + b can be interpreted as a binary operation that combines a and b, in an algebraic sense, or it can be interpreted as the addition of b more units to a. Under the latter interpretation, the parts of a sum a + b play asymmetric roles, and the operation a + b is viewed as applying the unary operation +b to a. Instead of calling botha and b addends, it is more appropriate to call a the augend in this case, since a plays a passive role. The unary view is also useful when discussing subtraction, because each unary addition operation has an inverse unary subtraction operation, and vice versa.

[edit]Properties

[edit]Commutativity

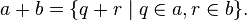

Addition is commutative, meaning that one can reverse the terms in a sum left-to-right, and the result will be the same as the last one. Symbolically, if a and b are any two numbers, then

- a + b = b + a.

The fact that addition is commutative is known as the "commutative law of addition". This phrase suggests that there are other commutative laws: for example, there is a commutative law of multiplication. However, many binary operations are not commutative, such as subtraction and division, so it is misleading to speak of an unqualified "commutative law".

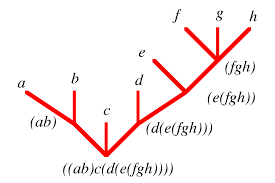

[edit]Associativity

A somewhat subtler property of addition is associativity, which comes up when one tries to define repeated addition. Should the expression

- "a + b + c"

be defined to mean (a + b) + c or a + (b + c)? That addition is associative tells us that the choice of definition is irrelevant. For any three numbers a, b, and c, it is true that

- (a + b) + c = a + (b + c).

For example, (1 + 2) + 3 = 3 + 3 = 6 = 1 + 5 = 1 + (2 + 3). Not all operations are associative, so in expressions with other operations like subtraction, it is important to specify the order of operations.

[edit]Zero and one

When adding zero to any number, the quantity does not change; zero is the identity element for addition, also known as the additive identity. In symbols, for any a,

- a + 0 = 0 + a = a.

This law was first identified in Brahmagupta's Brahmasphutasiddhanta in 628, although he wrote it as three separate laws, depending on whether a is negative, positive, or zero itself, and he used words rather than algebraic symbols. Later Indian mathematicians refined the concept; around the year 830, Mahavira wrote, "zero becomes the same as what is added to it", corresponding to the unary statement 0 + a = a. In the 12th century, Bhaskara wrote, "In the addition of cipher, or subtraction of it, the quantity, positive or negative, remains the same", corresponding to the unary statement a + 0 = a.[10]

In the context of integers, addition of one also plays a special role: for any integer a, the integer (a + 1) is the least integer greater than a, also known as the successor of a. Because of this succession, the value of some a + b can also be seen as the bth successor of a, making addition iterated succession.

[edit]Units

To numerically add physical quantities with units, they must first be expressed with common units. For example, if a measure of 5 feet is extended by 2 inches, the sum is 62 inches, since 60 inches is synonymous with 5 feet. On the other hand, it is usually meaningless to try to add 3 meters and 4 square meters, since those units are incomparable; this sort of consideration is fundamental in dimensional analysis.

[edit]Performing addition

[edit]Innate ability

Studies on mathematical development starting around the 1980s have exploited the phenomenon of habituation: infants look longer at situations that are unexpected.[11] A seminal experiment by Karen Wynn in 1992 involving Mickey Mouse dolls manipulated behind a screen demonstrated that five-month-old infants expect 1 + 1 to be 2, and they are comparatively surprised when a physical situation seems to imply that 1 + 1 is either 1 or 3. This finding has since been affirmed by a variety of laboratories using different methodologies.[12] Another 1992 experiment with older toddlers, between 18 to 35 months, exploited their development of motor control by allowing them to retrieve ping-pong balls from a box; the youngest responded well for small numbers, while older subjects were able to compute sums up to 5.[13]

Even some nonhuman animals show a limited ability to add, particularly primates. In a 1995 experiment imitating Wynn's 1992 result (but using eggplants instead of dolls), rhesus macaques and cottontop tamarins performed similarly to human infants. More dramatically, after being taught the meanings of the Arabic numerals 0 through 4, one chimpanzee was able to compute the sum of two numerals without further training.[14]

[edit]Elementary methods

Typically children master the art of counting first. When asked a problem requiring two items and three items to be combined, young children will model the situation with physical objects, often fingers or a drawing, and then count the total. As they gain experience, they will learn or discover the strategy of "counting-on": asked to find two plus three, children count three past two, saying "three, four, five" (usually ticking off fingers), and arriving at five. This strategy seems almost universal; children can easily pick it up from peers or teachers.[15]Most discover it independently. With additional experience, children learn to add more quickly by exploiting the commutativity of addition by counting up from the larger number, in this case starting with three and counting "four, five." Eventually children begin to recall certain addition facts ("number bonds"), either through experience or rote memorization. Once some facts are committed to memory, children begin to derive unknown facts from known ones. For example, a child who is asked to add six and seven may know that 6+6=12 and then reason that 6+7 will be one more, or 13.[16] Such derived facts can be found very quickly and most elementary school children eventually rely on a mixture of memorized and derived facts to add fluently.[17]

[edit]Decimal system

The prerequisite to addition in the decimal system is the fluent recall or derivation of the 100 single-digit "addition facts". One could memorize all the facts by rote, but pattern-based strategies are more enlightening and, for most people, more efficient:[18]

- One or two more: Adding 1 or 2 is a basic task, and it can be accomplished through counting on or, ultimately, intuition.[18]

- Zero: Since zero is the additive identity, adding zero is trivial. Nonetheless, some children are introduced to addition as a process that always increases the addends; word problemsmay help rationalize the "exception" of zero.[18]

- Doubles: Adding a number to itself is related to counting by two and to multiplication. Doubles facts form a backbone for many related facts, and fortunately, children find them relatively easy to grasp.[18]

- Near-doubles: Sums such as 6+7=13 can be quickly derived from the doubles fact 6+6=12 by adding one more, or from 7+7=14 but subtracting one.[18]

- Five and ten: Sums of the form 5+x and 10+x are usually memorized early and can be used for deriving other facts. For example, 6+7=13 can be derived from 5+7=12 by adding one more.[18]

- Making ten: An advanced strategy uses 10 as an intermediate for sums involving 8 or 9; for example, 8 + 6 = 8 + 2 + 4 = 10 + 4 = 14.[18]

As children grow older, they will commit more facts to memory, and learn to derive other facts rapidly and fluently. Many children never commit all the facts to memory, but can still find any basic fact quickly.[17]

The standard algorithm for adding multidigit numbers is to align the addends vertically and add the columns, starting from the ones column on the right. If a column exceeds ten, the extra digit is "carried" into the next column.[19] An alternate strategy starts adding from the most significant digit on the left; this route makes carrying a little clumsier, but it is faster at getting a rough estimate of the sum. There are many other alternative methods.

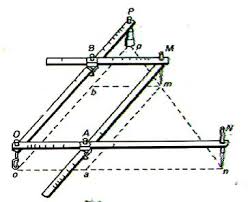

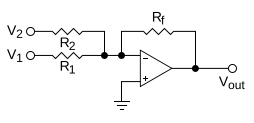

[edit]Computers

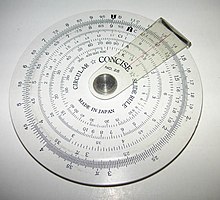

Analog computers work directly with physical quantities, so their addition mechanisms depend on the form of the addends. A mechanical adder might represent two addends as the positions of sliding blocks, in which case they can be added with an averaging lever. If the addends are the rotation speeds of two shafts, they can be added with a differential. A hydraulic adder can add the pressures in two chambers by exploiting Newton's second law to balance forces on an assembly of pistons. The most common situation for a general-purpose analog computer is to add two voltages (referenced to ground); this can be accomplished roughly with a resistor network, but a better design exploits an operational amplifier.[20]

Addition is also fundamental to the operation of digital computers, where the efficiency of addition, in particular the carry mechanism, is an important limitation to overall performance.

Adding machines, mechanical calculators whose primary function was addition, were the earliest automatic, digital computers. Wilhelm Schickard's 1623 Calculating Clock could add and subtract, but it was severely limited by an awkward carry mechanism. Burnt during its construction in 1624 and unknown to the world for more than three centuries, it was rediscovered in 1957[21] and therefore had no impact on the development of mechanical calculators.[22] Blaise Pascal invented the mechanical calculator in 1642[23] with an ingenious gravity-assisted carry mechanism. Pascal's calculator was limited by its carry mechanism in a different sense: its wheels turned only one way, so it could add but not subtract, except by the method of complements. By 1674 Gottfried Leibniz made the first mechanical multiplier; it was still powered, if not motivated, by addition.[24]

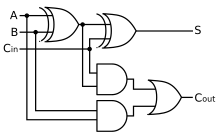

Adders execute integer addition in electronic digital computers, usually using binary arithmetic. The simplest architecture is the ripple carry adder, which follows the standard multi-digit algorithm taught to children. One slight improvement is the carry skip design, again following human intuition; one does not perform all the carries in computing 999 + 1, but one bypasses the group of 9s and skips to the answer.[25]

Since they compute digits one at a time, the above methods are too slow for most modern purposes. In modern digital computers, integer addition is typically the fastest arithmetic instruction, yet it has the largest impact on performance, since it underlies all the floating-point operations as well as such basic tasks as address generation during memory access and fetching instructions during branching. To increase speed, modern designs calculate digits in parallel; these schemes go by such names as carry select, carry lookahead, and the Ling pseudocarry. Almost all modern implementations are, in fact, hybrids of these last three designs.[26]

Unlike addition on paper, addition on a computer often changes the addends. On the ancient abacus and adding board, both addends are destroyed, leaving only the sum. The influence of the abacus on mathematical thinking was strong enough that early Latin texts often claimed that in the process of adding "a number to a number", both numbers vanish.[27] In modern times, the ADD instruction of a microprocessor replaces the augend with the sum but preserves the addend.[28] In a high-level programming language, evaluating a + b does not change either a or b; to change the value of a one uses the addition assignment operator a += b.

[edit]Addition of natural and real numbers

To prove the usual properties of addition, one must first define addition for the context in question. Addition is first defined on the natural numbers. In set theory, addition is then extended to progressively larger sets that include the natural numbers: the integers, the rational numbers, and the real numbers.[29] (In mathematics education,[30] positive fractions are added before negative numbers are even considered; this is also the historical route.[31])

[edit]Natural numbers

There are two popular ways to define the sum of two natural numbers a and b. If one defines natural numbers to be the cardinalities of finite sets, (the cardinality of a set is the number of elements in the set), then it is appropriate to define their sum as follows:

- Let N(S) be the cardinality of a set S. Take two disjoint sets A and B, with N(A) = a and N(B) = b. Then a + b is defined as

.[32]

.[32]

Here, A U B is the union of A and B. An alternate version of this definition allows A and B to possibly overlap and then takes their disjoint union, a mechanism that allows common elements to be separated out and therefore counted twice.

The other popular definition is recursive:

- Let n+ be the successor of n, that is the number following n in the natural numbers, so 0+=1, 1+=2. Define a + 0 = a. Define the general sum recursively by a + (b+) = (a + b)+. Hence 1+1=1+0+=(1+0)+=1+=2.[33]

Again, there are minor variations upon this definition in the literature. Taken literally, the above definition is an application of the Recursion Theorem on the poset N2.[34] On the other hand, some sources prefer to use a restricted Recursion Theorem that applies only to the set of natural numbers. One then considers a to be temporarily "fixed", applies recursion on bto define a function "a + ", and pastes these unary operations for all a together to form the full binary operation.[35]

This recursive formulation of addition was developed by Dedekind as early as 1854, and he would expand upon it in the following decades.[36] He proved the associative and commutative properties, among others, through mathematical induction; for examples of such inductive proofs, see Addition of natural numbers.

[edit]Integers

The simplest conception of an integer is that it consists of an absolute value (which is a natural number) and a sign (generally either positive ornegative). The integer zero is a special third case, being neither positive nor negative. The corresponding definition of addition must proceed by cases:

- For an integer n, let |n| be its absolute value. Let a and b be integers. If either a or b is zero, treat it as an identity. If a and b are both positive, define a + b = |a| + |b|. If a and b are both negative, define a + b = −(|a|+|b|). If a and b have different signs, define a + b to be the difference between |a| and |b|, with the sign of the term whose absolute value is larger.[37]

Although this definition can be useful for concrete problems, it is far too complicated to produce elegant general proofs; there are too many cases to consider.

A much more convenient conception of the integers is the Grothendieck group construction. The essential observation is that every integer can be expressed (not uniquely) as the difference of two natural numbers, so we may as well define an integer as the difference of two natural numbers. Addition is then defined to be compatible with subtraction:

- Given two integers a − b and c − d, where a, b, c, and d are natural numbers, define (a − b) + (c − d) = (a + c) − (b + d).[38]

[edit]Rational numbers (Fractions)

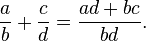

Addition of rational numbers can be computed using the least common denominator, but a conceptually simpler definition involves only integer addition and multiplication:

- Define

The commutativity and associativity of rational addition is an easy consequence of the laws of integer arithmetic.[39] For a more rigorous and general discussion, see field of fractions.

[edit]Real numbers

A common construction of the set of real numbers is the Dedekind completion of the set of rational numbers. A real number is defined to be aDedekind cut of rationals: a non-empty set of rationals that is closed downward and has no greatest element. The sum of real numbers aand b is defined element by element:

- Define

[40]

[40]

This definition was first published, in a slightly modified form, by Richard Dedekind in 1872.[41] The commutativity and associativity of real addition are immediate; defining the real number 0 to be the set of negative rationals, it is easily seen to be the additive identity. Probably the trickiest part of this construction pertaining to addition is the definition of additive inverses.[42]

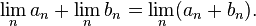

Unfortunately, dealing with multiplication of Dedekind cuts is a case-by-case nightmare similar to the addition of signed integers. Another approach is the metric completion of the rational numbers. A real number is essentially defined to be the a limit of a Cauchy sequence of rationals, lim an. Addition is defined term by term:

- Define

[43]

[43]

This definition was first published by Georg Cantor, also in 1872, although his formalism was slightly different.[44] One must prove that this operation is well-defined, dealing with co-Cauchy sequences. Once that task is done, all the properties of real addition follow immediately from the properties of rational numbers. Furthermore, the other arithmetic operations, including multiplication, have straightforward, analogous definitions.[45]

[edit]Generalizations

- There are many things that can be added: numbers, vectors, matrices, spaces, shapes, sets, functions, equations, strings, chains...—Alexander Bogomolny

There are many binary operations that can be viewed as generalizations of the addition operation on the real numbers. The field ofabstract algebra is centrally concerned with such generalized operations, and they also appear in set theory and category theory.

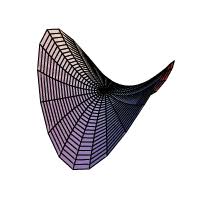

[edit]Addition in abstract algebra

In linear algebra, a vector space is an algebraic structure that allows for adding any two vectors and for scaling vectors. A familiar vector space is the set of all ordered pairs of real numbers; the ordered pair (a,b) is interpreted as a vector from the origin in the Euclidean plane to the point (a,b) in the plane. The sum of two vectors is obtained by adding their individual coordinates:

- (a,b) + (c,d) = (a+c,b+d).

This addition operation is central to classical mechanics, in which vectors are interpreted as forces.

In modular arithmetic, the set of integers modulo 12 has twelve elements; it inherits an addition operation from the integers that is central to musical set theory. The set of integers modulo 2 has just two elements; the addition operation it inherits is known in Boolean logic as the "exclusive or" function. In geometry, the sum of two angle measures is often taken to be their sum as real numbers modulo 2π. This amounts to an addition operation on the circle, which in turn generalizes to addition operations on many-dimensional tori.

The general theory of abstract algebra allows an "addition" operation to be any associative and commutative operation on a set. Basic algebraic structures with such an addition operation include commutative monoids and abelian groups.

[edit]Addition in set theory and category theory

A far-reaching generalization of addition of natural numbers is the addition of ordinal numbers and cardinal numbers in set theory. These give two different generalizations of addition of natural numbers to the transfinite. Unlike most addition operations, addition of ordinal numbers is not commutative. Addition of cardinal numbers, however, is a commutative operation closely related to the disjoint union operation.

In category theory, disjoint union is seen as a particular case of the coproduct operation, and general coproducts are perhaps the most abstract of all the generalizations of addition. Some coproducts, such as Direct sum and Wedge sum, are named to evoke their connection with addition.

[edit]Related operations

[edit]Arithmetic

Subtraction can be thought of as a kind of addition—that is, the addition of an additive inverse. Subtraction is itself a sort of inverse to addition, in that adding x and subtracting x areinverse functions.

Given a set with an addition operation, one cannot always define a corresponding subtraction operation on that set; the set of natural numbers is a simple example. On the other hand, a subtraction operation uniquely determines an addition operation, an additive inverse operation, and an additive identity; for this reason, an additive group can be described as a set that is closed under subtraction.[46]

Multiplication can be thought of as repeated addition. If a single term x appears in a sum n times, then the sum is the product of n and x. If n is not a natural number, the product may still make sense; for example, multiplication by −1 yields the additive inverse of a number.

In the real and complex numbers, addition and multiplication can be interchanged by the exponential function:

- ea + b = ea eb.[47]

This identity allows multiplication to be carried out by consulting a table of logarithms and computing addition by hand; it also enables multiplication on a slide rule. The formula is still a good first-order approximation in the broad context of Lie groups, where it relates multiplication of infinitesimal group elements with addition of vectors in the associated Lie algebra.[48]

There are even more generalizations of multiplication than addition.[49] In general, multiplication operations always distribute over addition; this requirement is formalized in the definition of a ring. In some contexts, such as the integers, distributivity over addition and the existence of a multiplicative identity is enough to uniquely determine the multiplication operation. The distributive property also provides information about addition; by expanding the product (1 + 1)(a + b) in both ways, one concludes that addition is forced to be commutative. For this reason, ring addition is commutative in general.[50]

Division is an arithmetic operation remotely related to addition. Since a/b = a(b−1), division is right distributive over addition: (a + b) / c = a / c+ b / c.[51] However, division is not left distributive over addition; 1/ (2 + 2) is not the same as 1/2 + 1/2.

[edit]Ordering

The maximum operation "max (a, b)" is a binary operation similar to addition. In fact, if two nonnegative numbers a and b are of differentorders of magnitude, then their sum is approximately equal to their maximum. This approximation is extremely useful in the applications of mathematics, for example in truncating Taylor series. However, it presents a perpetual difficulty in numerical analysis, essentially since "max" is not invertible. If b is much greater than a, then a straightforward calculation of (a + b) − b can accumulate an unacceptable round-off error, perhaps even returning zero. See also Loss of significance.

The approximation becomes exact in a kind of infinite limit; if either a or b is an infinite cardinal number, their cardinal sum is exactly equal to the greater of the two.[53] Accordingly, there is no subtraction operation for infinite cardinals.[54]

Maximization is commutative and associative, like addition. Furthermore, since addition preserves the ordering of real numbers, addition distributes over "max" in the same way that multiplication distributes over addition:

- a + max (b, c) = max (a + b, a + c).

For these reasons, in tropical geometry one replaces multiplication with addition and addition with maximization. In this context, addition is called "tropical multiplication", maximization is called "tropical addition", and the tropical "additive identity" is negative infinity.[55] Some authors prefer to replace addition with minimization; then the additive identity is positive infinity.[56]

Tying these observations together, tropical addition is approximately related to regular addition through the logarithm:

- log (a + b) ≈ max (log a, log b),

which becomes more accurate as the base of the logarithm increases.[57] The approximation can be made exact by extracting a constant h, named by analogy with Planck's constantfrom quantum mechanics,[58] and taking the "classical limit" as h tends to zero:

In this sense, the maximum operation is a dequantized version of addition.[59]

[edit]Other ways to add

Incrementation, also known as the successor operation, is the addition of 1 to a number.

Summation describes the addition of arbitrarily many numbers, usually more than just two. It includes the idea of the sum of a single number, which is itself, and the empty sum, which is zero.[60] An infinite summation is a delicate procedure known as a series.[61]

Counting a finite set is equivalent to summing 1 over the set.

Integration is a kind of "summation" over a continuum, or more precisely and generally, over a differentiable manifold. Integration over a zero-dimensional manifold reduces to summation.

Linear combinations combine multiplication and summation; they are sums in which each term has a multiplier, usually a real or complex number. Linear combinations are especially useful in contexts where straightforward addition would violate some normalization rule, such as mixing of strategies in game theory or superposition of states in quantum mechanics.

Convolution is used to add two independent random variables defined by distribution functions. Its usual definition combines integration, subtraction, and multiplication. In general, convolution is useful as a kind of domain-side addition; by contrast, vector addition is a kind of range-side addition.

[edit]In literature

- In chapter 9 of Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass, the White Queen asks Alice, "And you do Addition? ... What's one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one?" Alice admits that she lost count, and the Red Queen declares, "She can't do Addition".

- In George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, the value of 2 + 2 is questioned; the State contends that if it declares 2 + 2 = 5, then it is so. See Two plus two make five for the history of this idea.

[edit]Notes

- ^ From Enderton (p.138): "...select two sets K and L with card K = 2 and card L = 3. Sets of fingers are handy; sets of apples are preferred by textbooks."

- ^ Devine et al. p.263

- ^ a b Schwartzman p.19

- ^ "Addend" is not a Latin word; in Latin it must be further conjugated, as in numerus addendus "the number to be added".

- ^ Karpinski pp.56–57, reproduced on p.104

- ^ Schwartzman (p.212) attributes adding upwards to theGreeks and Romans, saying it was about as common as adding downwards. On the other hand, Karpinski (p.103) writes that Leonard of Pisa "introduces the novelty of writing the sum above the addends"; it is unclear whether Karpinski is claiming this as an original invention or simply the introduction of the practice to Europe.

- ^ Karpinski pp.150–153

- ^ See Viro 2001 for an example of the sophistication involved in adding with sets of "fractional cardinality".

- ^ Adding it up (p.73) compares adding measuring rods to adding sets of cats: "For example, inches can be subdivided into parts, which are hard to tell from the wholes, except that they are shorter; whereas it is painful to cats to divide them into parts, and it seriously changes their nature."

- ^ Kaplan pp.69–71

- ^ Wynn p.5

- ^ Wynn p.15

- ^ Wynn p.17

- ^ Wynn p.19

- ^ F. Smith p.130

- ^ Carpenter, Thomas; Fennema, Elizabeth; Franke, Megan Loef; Levi, Linda; Empson, Susan (1999).Children's mathematics: Cognitively guided instruction. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. ISBN 0-325-00137-5.

- ^ a b Henry, Valerie J.; Brown, Richard S. (2008). "First-grade basic facts: An investigation into teaching and learning of an accelerated, high-demand memorization standard". Journal for Research in Mathematics Education 39 (2): 153–183. doi:10.2307/30034895.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fosnot and Dolk p. 99

- ^ The word "carry" may be inappropriate for education; Van de Walle (p.211) calls it "obsolete and conceptually misleading", preferring the word "trade".

- ^ Truitt and Rogers pp.1;44–49 and pp.2;77–78

- ^ Jean Marguin p. 48 (1994)

- ^ René Taton, p. 81 (1969)

- ^ Jean Marguin, p. 48 (1994) ; Quoting René Taton(1963)

- ^ Williams pp.122–140

- ^ Flynn and Overman pp.2, 8

- ^ Flynn and Overman pp.1–9

- ^ Karpinski pp.102–103

- ^ The identity of the augend and addend varies with architecture. For ADD in x86 see Horowitz and Hill p.679; for ADD in 68k see p.767.

- ^ Enderton chapters 4 and 5, for example, follow this development.

- ^ California standards; see grades 2, 3, and 4.

- ^ Baez (p.37) explains the historical development, in "stark contrast" with the set theory presentation: "Apparently, half an apple is easier to understand than a negative apple!"

- ^ Begle p.49, Johnson p.120, Devine et al. p.75

- ^ Enderton p.79

- ^ For a version that applies to any poset with thedescending chain condition, see Bergman p.100.

- ^ Enderton (p.79) observes, "But we want one binary operation +, not all these little one-place functions."

- ^ Ferreirós p.223

- ^ K. Smith p.234, Sparks and Rees p.66

- ^ Enderton p.92

- ^ The verifications are carried out in Enderton p.104 and sketched for a general field of fractions over a commutative ring in Dummit and Foote p.263.

- ^ Enderton p.114

- ^ Ferreirós p.135; see section 6 of Stetigkeit und irrationale Zahlen.

- ^ The intuitive approach, inverting every element of a cut and taking its complement, works only for irrational numbers; see Enderton p.117 for details.

- ^ Textbook constructions are usually not so cavalier with the "lim" symbol; see Burrill (p. 138) for a more careful, drawn-out development of addition with Cauchy sequences.

- ^ Ferreirós p.128

- ^ Burrill p.140

- ^ The set still must be nonempty. Dummit and Foote (p.48) discuss this criterion written multiplicatively.

- ^ Rudin p.178

- ^ Lee p.526, Proposition 20.9

- ^ Linderholm (p.49) observes, "By multiplication, properly speaking, a mathematician may mean practically anything. By addition he may mean a great variety of things, but not so great a variety as he will mean by 'multiplication'."

- ^ Dummit and Foote p.224. For this argument to work, one still must assume that addition is a group operation and that multiplication has an identity.

- ^ For an example of left and right distributivity, see Loday, especially p.15.

- ^ Compare Viro Figure 1 (p.2)

- ^ Enderton calls this statement the "Absorption Law of Cardinal Arithmetic"; it depends on the comparability of cardinals and therefore on the Axiom of Choice.

- ^ Enderton p.164

- ^ Mikhalkin p.1

- ^ Akian et al. p.4

- ^ Mikhalkin p.2

- ^ Litvinov et al. p.3

- ^ Viro p.4

- ^ Martin p.49

- ^ Stewart p.8

[edit]References

- History

- Bunt, Jones, and Bedient (1976). The historical roots of elementary mathematics. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-389015-5.

- Ferreirós, José (1999). Labyrinth of thought: A history of set theory and its role in modern mathematics. Birkhäuser. ISBN 0-8176-5749-5.

- Kaplan, Robert (2000). The nothing that is: A natural history of zero. Oxford UP. ISBN 0-19-512842-7.

- Karpinski, Louis (1925). The history of arithmetic. Rand McNally. LCC QA21.K3.

- Schwartzman, Steven (1994). The words of mathematics: An etymological dictionary of mathematical terms used in English. MAA. ISBN 0-88385-511-9.

- Williams, Michael (1985). A history of computing technology. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-389917-9.

- Elementary mathematics

- Davison, Landau, McCracken, and Thompson (1999). Mathematics: Explorations & Applications (TE ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-435817-1.

- F. Sparks and C. Rees (1979). A survey of basic mathematics. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-059902-5.

- Education

- Begle, Edward (1975). The mathematics of the elementary school. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-004325-6.

- California State Board of Education mathematics content standards Adopted December 1997, accessed December 2005.

- D. Devine, J. Olson, and M. Olson (1991). Elementary mathematics for teachers (2e ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-85947-8.

- National Research Council (2001). Adding it up: Helping children learn mathematics. National Academy Press. ISBN 0-309-06995-5.

- Van de Walle, John (2004). Elementary and middle school mathematics: Teaching developmentally (5e ed.). Pearson. ISBN 0-205-38689-X.

- Cognitive science

- Baroody and Tiilikainen (2003). "Two perspectives on addition development". The development of arithmetic concepts and skills. pp. 75. ISBN 0-8058-3155-X.

- Fosnot and Dolk (2001). Young mathematicians at work: Constructing number sense, addition, and subtraction. Heinemann. ISBN 0-325-00353-X.

- Weaver, J. Fred (1982). "Interpretations of number operations and symbolic representations of addition and subtraction". Addition and subtraction: A cognitive perspective. pp. 60.ISBN 0-89859-171-6.

- Wynn, Karen (1998). "Numerical competence in infants". The development of mathematical skills. pp. 3. ISBN 0-86377-816-X.

- Mathematical exposition

- Bogomolny, Alexander (1996). "Addition". Interactive Mathematics Miscellany and Puzzles (cut-the-knot.org). Retrieved 3 February 2006.

- Dunham, William (1994). The mathematical universe. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-53656-3.

- Johnson, Paul (1975). From sticks and stones: Personal adventures in mathematics. Science Research Associates. ISBN 0-574-19115-1.

- Linderholm, Carl (1971). Mathematics Made Difficult. Wolfe. ISBN 0-7234-0415-1.

- Smith, Frank (2002). The glass wall: Why mathematics can seem difficult. Teachers College Press. ISBN 0-8077-4242-2.

- Smith, Karl (1980). The nature of modern mathematics (3e ed.). Wadsworth. ISBN 0-8185-0352-1.

- Advanced mathematics

- Bergman, George (2005). An invitation to general algebra and universal constructions (2.3e ed.). General Printing. ISBN 0-9655211-4-1.

- Burrill, Claude (1967). Foundations of real numbers. McGraw-Hill. LCC QA248.B95.

- D. Dummit and R. Foote (1999). Abstract algebra (2e ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-36857-1.

- Enderton, Herbert (1977). Elements of set theory. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-238440-7.

- Lee, John (2003). Introduction to smooth manifolds. Springer. ISBN 0-387-95448-1.

- Martin, John (2003). Introduction to languages and the theory of computation (3e ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-232200-4.

- Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of mathematical analysis (3e ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-054235-X.

- Stewart, James (1999). Calculus: Early transcendentals (4e ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-36298-2.

- Mathematical research

- Akian, Bapat, and Gaubert (2005). "Min-plus methods in eigenvalue perturbation theory and generalised Lidskii-Vishik-Ljusternik theorem". INRIA reports. arXiv:math.SP/0402090.

- J. Baez and J. Dolan (2001). "From Finite Sets to Feynman Diagrams". Mathematics Unlimited— 2001 and Beyond. pp. 29. arXiv:math.QA/0004133. ISBN 3-540-66913-2.

- Litvinov, Maslov, and Sobolevskii (1999). Idempotent mathematics and interval analysis. Reliable Computing, Kluwer.

- Loday, Jean-Louis (2002). "Arithmetree". J. Of Algebra 258: 275. arXiv:math/0112034. doi:10.1016/S0021-8693(02)00510-0.

- Mikhalkin, Grigory (2006). "Tropical Geometry and its applications". To appear at the Madrid ICM. arXiv:math.AG/0601041.

- Viro, Oleg (2001), Dequantization of real algebraic geometry on logarithmic paper, in Cascuberta, Carles; Miró-Roig, Rosa Maria; Verdera, Joan et al., "European Congress of Mathematics: Barcelona, July 10–14, 2000, Volume I", Progress in Mathematics (Basel: Birkhäuser) 201: 135–146, arXiv:0005163, ISBN 3-7643-6417-3

- Computing

- M. Flynn and S. Oberman (2001). Advanced computer arithmetic design. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-41209-0.

- P. Horowitz and W. Hill (2001). The art of electronics (2e ed.). Cambridge UP. ISBN 0-521-37095-7.

- Jackson, Albert (1960). Analog computation. McGraw-Hill. LCC QA76.4 J3.

- T. Truitt and A. Rogers (1960). Basics of analog computers. John F. Rider. LCC QA76.4 T7.

- Marguin, Jean (1994) (in fr). Histoire des instruments et machines à calculer, trois siècles de mécanique pensante 1642-1942. Hermann. ISBN 978-2705661663.

- Taton, René (1963) (in fr). Le calcul mécanique. Que sais-je ? n° 367. Presses universitaires de France. pp. 20–28.

- Marguin, Jean (1994) (in fr). Histoire des instruments et machines à calculer, trois siècles de mécanique pensante 1642-1942. Hermann. ISBN 978-2705661663.

|

||||||||||

22:12 Publié dans Addition | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Arithmetic

Arithmetic

Arithmetic or arithmetics (from the Greek word ἀριθμός = number) is the oldest and most elementary branch of mathematics, used by almost everyone, for tasks ranging from simple day-to-day counting to advanced science and business calculations. It involves the study of quantity, especially as the result of combining numbers. In common usage, it refers to the simpler properties when using the traditional operations ofaddition, subtraction, multiplication and division with smaller values of numbers. Professional mathematicians sometimes use the term (higher) arithmetic[1] when referring to more advanced results related to number theory, but this should not be confused with elementary arithmetic.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]History

The prehistory of arithmetic is limited to a very small number of small artifacts which may indicate conception of addition and subtraction, the best-known being the Ishango bone fromcentral Africa, dating from somewhere between 20,000 and 18,000 BC although its interpretation is disputed.[2]

The earliest written records indicate the Egyptians and Babylonians used all the elementary arithmetic operations as early as 2000 BC. These artifacts do not always reveal the specific process used for solving problems, but the characteristics of the particular numeral system strongly influence the complexity of the methods. The hieroglyphic system for Egyptian numerals, like the later Roman numerals, descended from tally marks used for counting. In both cases, this origin resulted in values that used a decimal base but did not includepositional notation. Although addition was generally straightforward, multiplication in Roman arithmetic required the assistance of a counting board to obtain the results.

Early number systems that included positional notation were not decimal, including the sexagesimal (base 60) system for Babylonian numerals and the vigesimal(base 20) system that defined Maya numerals. Because of this place-value concept, the ability to reuse the same digits for different values contributed to simpler and more efficient methods of calculation.

The continuous historical development of modern arithmetic starts with the Hellenistic civilization of ancient Greece, although it originated much later than the Babylonian and Egyptian examples. Prior to the works of Euclid around 300 BC, Greek studies in mathematics overlapped with philosophical and mystical beliefs. For example, Nicomachus summarized the viewpoint of the earlier Pythagorean approach to numbers, and their relationships to each other, in his Introduction to Arithmetic.

Greek numerals, derived from the hieratic Egyptian system, also lacked positional notation, and therefore imposed the same complexity on the basic operations of arithmetic. For example, the ancient mathematician Archimedes devoted his entire work The Sand Reckoner merely to devising a notation for a certain large integer.