17/04/2011

Puiseux series

Puiseux series

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Puiseux's theorem)

|

This article may be too technical for most readers to understand. Please improve this article to make it understandable to non-experts, without removing the technical details. Reason: The article should start by providing examples, definitions, and theorems in the setting of undergraduate-level complex analysis, which will make it useful to a fairly wide audience (engineers, physicists, mathematics undergraduates, etc.). Only after that should it provide the formulation informed by modern algebra (involving concepts such as "functor," "union of fields," "direct limit," etc.), which is useful only to a much narrower audience. (April 2011) |

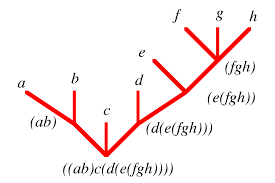

In mathematics, Puiseux series are a generalization of formal power series, first introduced by Isaac Newton in 1676[1] and rediscovered by Victor Puiseux in 1850,[2] that allows for negative and fractional exponents of the indeterminate. The field of Puiseux series is a (functorial) construction which, for any field (of coefficients) K, gives a field

containing the field of formal Laurent series, and which is algebraically closed of characteristic 0 when K is so (a statement usually referred to as Puiseux's theorem or sometimes theNewton–Puiseux theorem). The Puiseux expansion is a generalization of the Laurent series expansion (hence also of the formal series expansion), initially defined for algebraic functions or (equivalently) branches of algebraic curves (a fact also referred to as Puiseux's theorem) and which can be generalized to various settings.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]Field of Puiseux series

If K is a field then we can define the field of Puiseux series with coefficients in K (or over K) informally as the set of formal expressions of the form

where n and k0 are a nonzero natural number and an integer respectively (which are part of the datum of f): in other words, Puiseux series differ from formal Laurent series in that they allow for fractional exponents of the indeterminate as long as these fractional exponents have bounded denominator (here n), and just as Laurent series, Puiseux series allow for negative exponents of the indeterminate as long as these negative exponents are bounded (here by k0). Addition and multiplication are as expected: one might define them by first “upgrading” the denominator of the exponents to some common denominator and then performing the operation in the corresponding field of formal Laurent series.

In other words, the field of Puiseux series with coefficients in K is the union of the fields K((T1 / n)) (where n ranges over the nonzero natural numbers), where each element of the union is a field of formal Laurent series over T1 / n (considered as an indeterminate), and where each such field is considered as a subfield of the ones with larger n by rewriting the fractional exponents to use a larger denominator (e.g., T1 / 2 is identified with T15 / 30 as expected).

This yields a formal definition of the field of Puiseux series: it is the direct limit of the direct system, indexed over the non-zero natural numbers n ordered by divisibility, whose objects are all K((T)) (the field of formal Laurent series, which we rewrite as

K((Tn)) for clarity),

with a morphism

being given, whenever m divides n, by .

[edit]Valuation and order

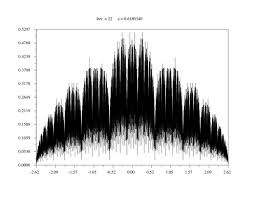

The Puiseux series over a field K form a valued field with value group (the rationals): the valuation v(f) of a series

as above is defined to be the smallest rational k / n such that the coefficient ck of the term with exponent k / n is non-zero (with the usual convention that the valuation of 0 is +∞). The coefficient ck in question is typically called the valuation coefficient of f.

This valuation in turn defines a (translation-invariant) distance (which is ultrametric), hence a topology on the field of Puiseux series by letting the distance from f to 0 be exp( − v(f)). This justifies a posteriori the notation

as the series in question does, indeed, converge to f in the Puiseux series field (this is in contrast to Hahn series which cannot be viewed as converging series).

If the base field K is ordered, then the field of Puiseux series over K is also naturally (“lexicographically”) ordered as follows: a non-zero Puiseux series f with 0 is declared positive whenever its valuation coefficient is so. Essentially, this means that any positive rational power of the indeterminate T is made positive, but smaller than any positive element in the base field K.

If the base field K is endowed with a valuation w, then we can construct a different valuation on the field of Puiseux series over K by letting the valuation

of be

where v = k / n is the previously defined valuation (ck is the first non-zero coefficient) and ω is infinitely large (in other words, the value group of is ordered lexicographically, where Γ is the value group of w). Essentially, this means that the previously defined valuation v is corrected by an infinitesimal amount to take into account the valuation w given on the base field.

[edit]Algebraic closedness of Puiseux series

One essential property of Puiseux series is expressed by the following theorem, attributed to Puiseux[2] (for ) but which was implicit in Newton's use of the Newton polygon as early as 1671[3] and therefore known either as Puiseux's theorem or as the Newton–Puiseux theorem[4]:

Theorem: if K is an algebraically closed field of characteristic zero, then the field of Puiseux series over K is the algebraic closure of the field of formal Laurent series over K.[5]

Very roughly, the proof proceeds essentially by inspecting the Newton polygon of the equation and extracting the coefficients one by one using a valuative form of Newton's method. Provided algebraic equations can be solved algorithmically in the base field K, then the coefficients of the Puiseux series solutions can be computed to any given order.

For example, the equation X2 − X = T − 1 has solutions

and

(one readily checks on the first few terms that the sum and product of these two series are 1 and T − 1 respectively): this is valid whenever the base field K has characteristic different from 2.

As the powers of 2 in the denominators of the coefficients of the previous example might lead one to believe, the statement of the theorem is not true in positive characteristic. The example of the Artin Schreier equation Xp − X = T − 1 shows this: reasoning with valuations shows that X should have valuation , and if we rewrite it as X = T − 1 / p + X1 then

, so

and one shows similarly that X1 should have valuation , and proceeding in that way one obtains the series

;

since this series makes no sense as a Puiseux series—because the exponents have unbounded denominators— the original equation has no solution. However, such Eisenstein equations are essentially the only ones not to have a solution, because, if K is algebraically closed of characteristic p>0, then the field of Puiseux series over K is the perfect closure of the maximal tamely ramified extension of K[4].

Similarly to the case of algebraic closure, there is an analogous theorem for real closure: if K is a real closed field, then the field of Puiseux series over K is the real closure of the field of formal Laurent series over K.[6] (This implies the former theorem since any algebraically closed field of characteristic zero is the unique quadratic extension of some real-closed field.)

There is also an analogous result for p-adic closure: if K is a p-adically closed field with respect to a valuation w, then the field of Puiseux series over K is also p-adically closed.[7]

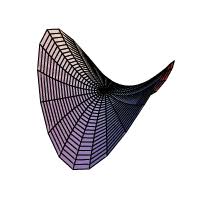

[edit]Puiseux expansion of algebraic curves and functions

[edit]Algebraic curves

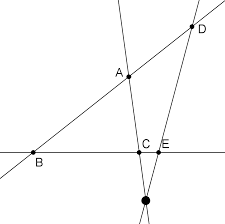

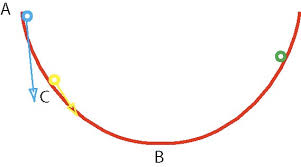

Let X be an algebraic curve[8] given by an affine equation F(x,y) = 0 over an algebraically closed field K of characteristic zero, and consider a point p on X which we can assume to be (0,0). We also assume that X is not the coordinate axis x=0. Then a Puiseux expansion of (the y coordinate of) X at p is a Puiseux series f having positive valuation such thatF(x,f(x)) = 0.

More precisely, let us define the branches of X at p to be the points q of the normalization Y of X which map to p. For each such q, there is a local coordinate t of Y at q (which is a smooth point) such that the coordinates x and y can be expressed as formal power series of t, say (since K is algebraically closed, we can assume the valuation coefficient to be 1) and : then there is a unique Puiseux series of the form (a power series in T1 / n), such that y(t) = f(x(t)) (the latter expression is meaningful since is a well defined power series in t). This is a Puiseux expansion of X at p which is said to be associated to the branch given by q(or simply, the Puiseux expansion of that branch of X), and each Puiseux expansion of X at p is given in this manner for a unique branch of X at p.[9][10]

This existence of a formal parametrization of the branches of an algebraic curve or function is also referred to as Puiseux's theorem: it has arguably the same mathematical content as the fact that the field of Puiseux series is algebraically closed and is a historically more accurate description of the original author's statement[11].

For example, the curve y2 = x3 + x2 (whose normalization is a line with coordinate t and map ) has two branches at the double point (0,0), corresponding to the points t=+1 and t=−1 on the normalization, whose Puiseux expansions are and respectively (here, both are power series because the x coordinate is étale at the corresponding points in the normalization). At the smooth point (-1,0) (which is t=0 in the normalization), it has a single branch, given by the Puiseux expansion y = − (x + 1)1 / 2 + (x + 1)3 / 2 (the x coordinate ramifies at this point, so it is not a power series).

The curve y2 = x3 (whose normalization is again a line with coordinate t and map ), on the other hand, has a single branch at the cusp point (0,0), whose Puiseux expansion is y = x3 / 2.

[edit]Analytic convergence

When , i.e. the field of complex numbers, the Puiseux expansions defined above are convergent in the sense that for a given choice of n-th root of x, they converge for small enough | x | , hence define an analytic parametrization of each branch of X in the neighborhood of p (more precisely, the parametrization is by the n-th root of x).

[edit]Generalization

The field of Puiseux series is not complete, but its completion can be easily described: it is the field of formal expressions of the form , where the support of the coefficients (that is, the set of e such that ) is the range of an increasing sequence of rational numbers that either is finite or tends to +∞. In other words, such series admit exponents of unbounded denominators, provided there are finitely many terms of exponent less than A for any given bound A. For example, is not a Puiseux series, but it is the limit of a Cauchy sequence of Puiseux series (Puiseux polynomials). However, even this completion is still not "maximally complete" in the sense that it admits non-trivial extensions which are valued fields having the same value group and residue field[12][13], hence the opportunity of completing it even more:

Hahn series are a further (larger) generalization of Puiseux series, introduced by Hans Hahn (in the course of the proof of his embedding theorem in 1907 and then studied by him in his approach to Hilbert's seventeenth problem), where instead of requiring the exponents to have bounded denominator they are required to form a well-ordered subset of the value group (usually or ). These were later further generalized by Anatoly Maltsev and Bernhard Neumann to a non-commutative setting (they are therefore sometimes known as Hahn-Mal'cev-Neumann series). Using Hahn series, it is possible to give a description of the algebraic closure of the field of power series in positive characteristic which is somewhat analogous to the field of Puiseux series.[14]

[edit]Notes

- ^ Newton (1960)

- ^ a b Puiseux (1850, 1851)

- ^ Newton (1736)

- ^ a b cf. Kedlaya (2001), introduction

- ^ cf. Eisenbud (1995), corollary 13.15 (p. 295)

- ^ Basu &al (2006), chapter 2 (“Real Closed Fields”), theorem 2.91 (p. 75)

- ^ Cherlin (1976), chapter 2 (“The Ax–Kochen–Ershof Transfer Principle”), §7 (“Puiseux series fields”)

- ^ We assume that X is irreducible or, at least, that it is reduced and that it does not contain the y coordinate axis.

- ^ Shafarevich (1994), II.5, p. 133–135

- ^ Cutkosky (2004), chapter 2, p. 3–11

- ^ Puiseux (1850), p. 397

- ^ Poonen, Bjorn (1993). "Maximally complete fields". Enseign. Math. 39: 87–106.

- ^ Kaplansky, Irving (1942). "Maximal Fields with Valuations". Duke Math. J. 9: 393–321.

- ^ Kedlaya (2001)

[edit]References

- Basu, Saugata; Pollack, Richard; Roy, Marie-Françoise (2006). Algorithms in Real Algebraic Geometry. Algorithms and Computations in Mathematics 10 (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/3-540-33099-2. ISBN 978-3-540-33098-1.

- Cherlin, Greg (1976). Model Theoretic Algebra Selected Topics. Lecture Notes in Mathematics 521. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-07696-4.

- Cutkosky, Steven Dale (2004). Resolution of Singularities. Graduate Studies in Mathematics 63. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0821835556.

- Eisenbud, David (1995). Commutative Algebra with a View Toward Algebraic Geometry. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 150. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-94269-6.

- Kedlaya, Kiran Sridhara (2001). "The algebraic closure of the power series field in positive characteristic". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 129: 3461–3470. doi:10.1090/S0002-9939-01-06001-4

- Newton, Isaac (1671). The method of fluxions and infinite series; with its application to the geometry of curve-lines (translated from Latin and published by John Colson in 1736)

- Newton, Isaac (1960). "letter to Oldenburg dated 1676 Oct 24". The correspondence of Isaac Newton. II. Cambridge University press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0521087228

- Puiseux, Victor Alexandre (1850). "Recherches sur les fonctions algébriques". J. Math. Pures Appl. 15: 365–480

- Puiseux, Victor Alexandre (1851). "Recherches sur les fonctions algébriques". J. Math. Pures Appl. 16: 228–240

- Shafarevich, Igor Rostislavovich (1994). Basic Algebraic Geometry (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-54812-2.

- Puiseux series at MathWorld

- Puiseux's Theorem at MathWorld

- Puiseux series at PlanetMath

[edit]External links

Categories: Commutative algebra | Algebraic curves

08:08 Publié dans Puiseux series | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Les commentaires sont fermés.